The declining public face of religion

At one point, religion served as an integral part of society for people worldwide, but now there are many accounts of decreasing religiosity. The process of secularization and the decline of religion in the public sphere are happening most clearly in European countries, such as Norway. As religious radio programming from the state has shifted, so has the way individuals privately practice their religion. How does this impact the religious identity of Norway as a whole?

The Modeling Religious Change (MRC) project is dedicated to using a variety of technologies such as data sets, simulation, and computer modeling to study religious identity and change. This unique approach allows our researchers to analyze interactions between complex factors and understand how religion is changing in different cultural contexts.

Like other Nordic countries, Norway has a state church — the Lutheran State Church — and a state-sponsored media system — the NRK. When the NRK started broadcasting channels in the early 20th century, the church had a strong influence on daily life through the media.

However, institutional religion may be on the decline in Norway. The State Church in Norway is not retaining the influence and support it once had in society, but religion remains an important aspect of life for Norwegians. The majority of people are still members of the State Church. And although church attendance is rare, some Norwegians still tune in to the broadcasts of religious media.

MRC researchers have crafted multiple dimensions of religiosity to analyze religious change in a way that accounts for varying cultural, economic, and social contexts of the countries we study. We define private practice as the private habits individuals maintain (this includes rituals, meditation, reading scripture, prayer, personal offerings, and consuming religious media) and public practice as how regularly individuals engage with a religious community and its rituals (most often service attendance).

Among the dimensions of religiosity, private religious practice is particularly important in Norway given that private aspects of religiosity are seemingly taking precedence over the public displays. As the institutional components of religion are deemphasized in a secular society, there is a trend toward individualization in religious practices.

Private religious practice

Typically, one thinks of prayer when it comes to private religious practice. Many people pray in their homes when they wake up, before meals, before bed, and at various points during the day.

My grandmother grew up Catholic and always expressed the importance of her faith to her personally, but we rarely attended Church unless it was an important holiday like Christmas or Easter. It was clear that public worship did not hold the utmost importance to my grandmother, yet her Bible and rosary sat on her nightstand as symbols of the importance of religion to her. I would often see her praying the rosary early in the morning or at night before bed, and she always encouraged me to join and take up the practice myself.

This is not an uncommon trend worldwide. While the public aspects of religious traditions may be declining, private aspects of religion remain important for individual religiosity. Because few historic surveys ask Norwegians how often they pray, we rely on a variety of qualitative sources and nontraditional measures, such as engagement with religious media, to paint the picture of private practice trends in Norway. Survey data compiled by our researchers identifies the habitual nature of using religious media among older generations of Norwegians.

Church controlled media

The Lutheran State Church, which is recognized as the official religion, only started separating from the state in 2012. So, it comes as no surprise that state media crafted its messages with loyalty to the church throughout the 20th century. Prior to the 1990s, Norwegian media consisted of a single state-owned and regulated broadcasting company, the NRK. There was one television channel and one radio channel. Both adhered to the hegemonic position of the Church of Norway and muted any church criticism.

During the 1980s, Norwegian media underwent a series of transformations and began reformatting messages that were once influenced by loyalty to the religious institution. The process in which the media begins to gain authority as religious institutions lose authority is known as the mediatization of society.

In the 1990s, the Norwegian government passed legislation allowing for the establishment of two new nationwide radio channels outside of the NRK, marking the shift of media from the public sector to the private sector. This ‘great shift’ commercialized the media monopoly and enabled competition in programming.

Many worried that the media would seek to maximize profits rather than operate as a cultural institution that serves public interests. After all, as a public media service, the NRK benefitted from serving both minority and majority interests.

Religion still has a considerable presence in the media and increasingly reflects the growing religious diversity in Norway. Between 1980 and 2008, the percentage of stories covering news on the Church of Norway steadily dropped from 56% to 39%, while Islam news coverage increased from 3% to 13%. According to the NRK, continued broadcasting of religious programming is not due to church influence but due to the interest of listeners and viewers.

The presentation of religion in the public sphere has diversified and the creation of private media services allows the portrayal of less-organized religious voices in popular Norwegian media. The NRK now broadcasts various religious identities and ideologies, enabling people to develop or maintain practices suited to their preferences.

Praying to God or myself?

Through her research on two generations of women in Norway, sociologist Inger Furseth shows the stark difference between past and contemporary religiosity in increasingly and highly secular societies. She illustrates that the older generation still values traditional forms of religion while the younger generation leans more towards individualized expressions of spirituality.

In another study on Dutch prayer practices, researchers found a sharp contrast between traditional and contemporary forms of prayer. Traditional prayer acknowledges the existence of a personal God while contemporary forms of prayer are more meditative and spiritual, focusing on the self rather than a higher power.

Although church attendance and commitment are extremely low, up to 10% of the Norwegian population still listens to Christian worship through NRK regularly, according to data from 2014. In the study on Dutch prayer, the researchers stressed how contemporary prayers need not take place in a formal worship setting but are often said at ordinary places and times such as at home or in bed at night. Perhaps religious radio in Norway serves as a more private way for people to nourish their religiosity and spirituality from the comfort of their homes.

What does this transformation look like?

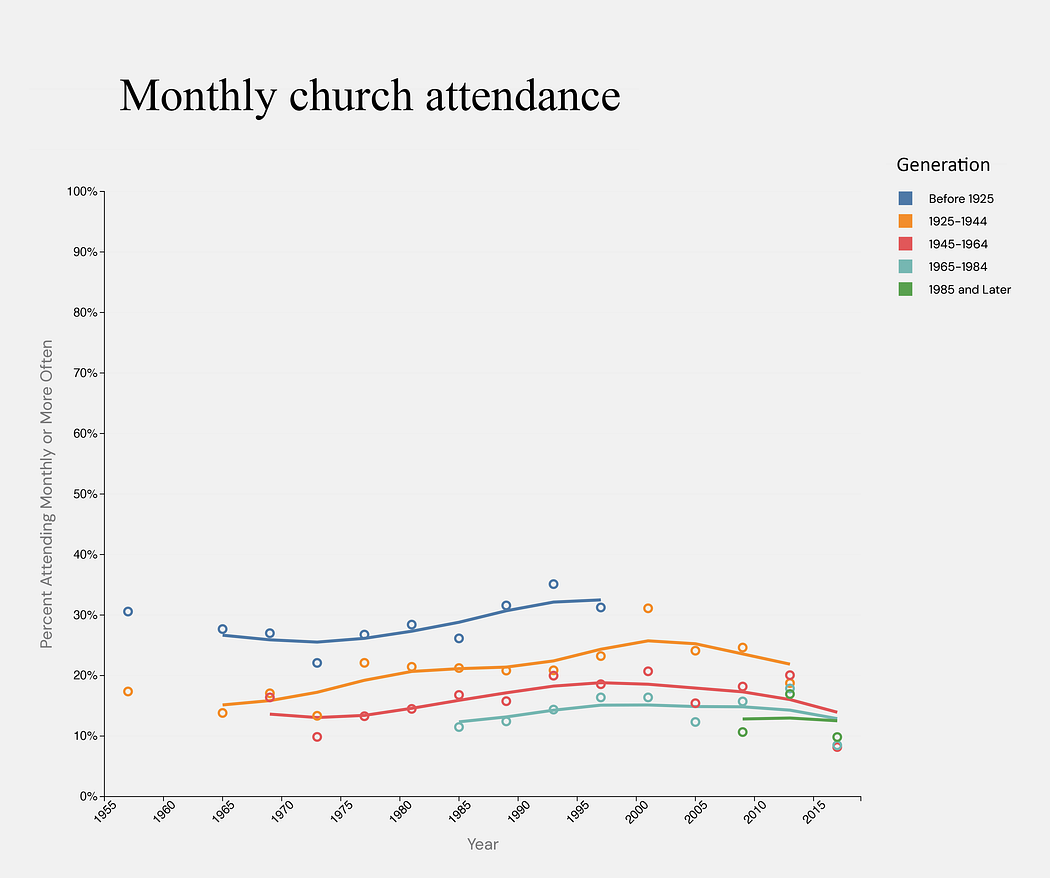

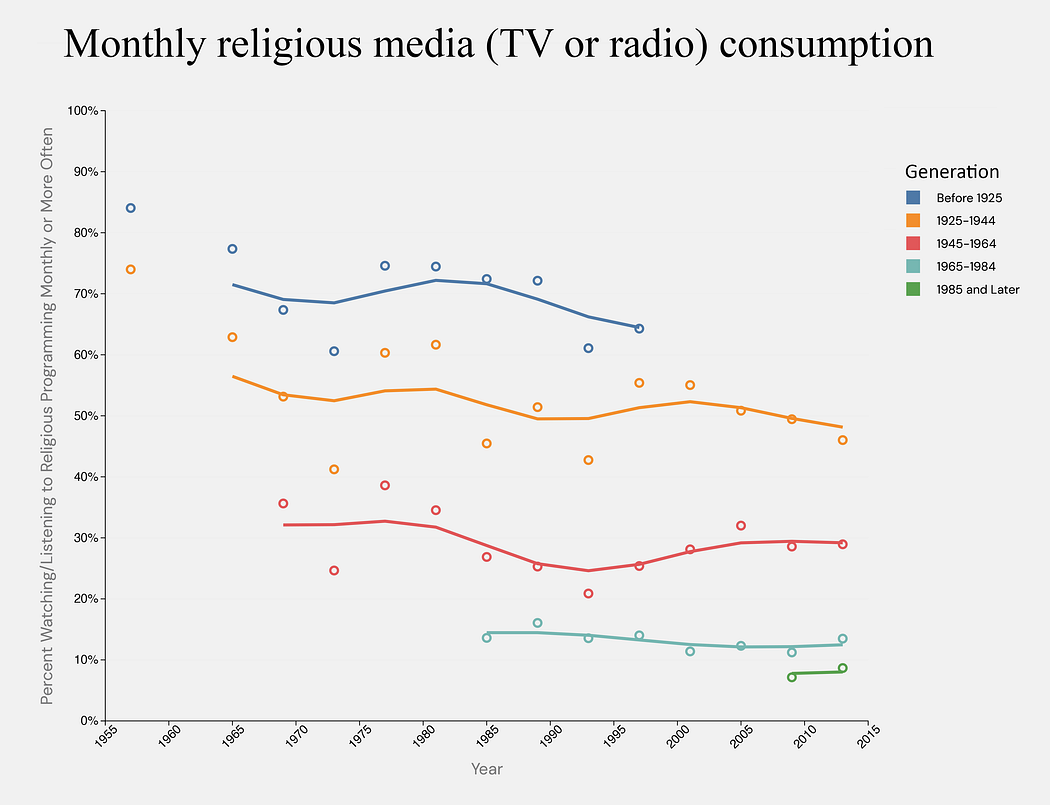

MRC researchers have synthesized multiple data sets to estimate how often Norwegians attend religious services and how often they listen to or watch them on television from any source, including the NRK. The Norwegian Election Survey has asked about these practices since 1957.

According to the Norwegian Election Survey data, monthly church attendance in Norway has been below 40% since the 1950s. Of those born after 1964, monthly attendance is only between 10–15%. Such generational decline suggests that low commitment to the public forms of worship in Norway has been normal for many decades and is likely to continue.

The percentage of Norwegians who report tuning in to religious media monthly or more, however, is much higher than church attendance. The majority of Norwegians born before 1945 engaged in religious media. But among those born in 1965 and later, their private worship engagement looks comparable to their public church attendance, at around 15% or less. These generations grew up during or after the privatization of Norwegian media and now rarely engage with the religious programming that is still available.

However, the percentage tuning in to religious media monthly or more has remained relatively consistent within each age group over time, suggesting the use of religious radio or television is a habitual practice, much like prayer. Even as the content of TV and radio has shifted, those who grew up using religious media maintain the habit. Among older people, tuning in to religious radio or television is more popular than public worship, highlighting the preference for individualized private religious expressions common to secularizing and diversifying societies.

The diverse dimensions of religiosity are grounded in the habits and practices of individuals that make up certain societies. By studying religious change in Norway through media, our researchers are better able to understand aspects of religious change in varying places, cultures, and times. It is a step towards predicting how religiosity will continue to change in a future where private religious practices are seemingly favored over public religiosity.