It has been long assumed that the attainment of higher education is a direct road towards declining religiosity. Past research suggests that higher education exposes students to new worldviews beyond the scope of the religion they grew up in, challenging the importance of their religious tradition and opening them up to non-religious perspectives.

However, this association between education and religion has been questioned by studies that show a positive association between more education and prayer, church participation, afterlife beliefs, and religious importance. Additionally, the religiously unaffiliated are now less likely to graduate from a higher education institution than in the past.

Does attending college or university actually reduce religiosity?

Or does increasing education have a positive impact on religiosity?

Which of these competing relationships between higher education and religiosity exist, and are there different patterns depending on what aspect of religiosity we examine?

A new study led by the Modeling Religious Change (MRC) project with the Center for Mind and Culture (CMAC) focused on these questions using longitudinal data on religiosity and education among young people in the United States. Our findings demonstrate that the education-religiosity relationship is far from simple.

The religious road to education

Some religious communities support their youth on the path toward higher education. When I attended a Catholic high school, college was pushed as the only option after graduation. This path was so engrained that I never questioned it. My school community was also my religious community, which meant I was immersed in a deep religious network receiving constant moral direction. Everyone monitored our behavior ensuring we did not skip class or assignments and kept our grades up.

The resources that we have in adolescence can influence us to take certain trajectories in life. For some adolescents, the question of attending college is not shaped only by economic circumstances and individual aspirations. Growing up in a religious environment may also account for the pursuit of higher education. Their social networks discourage risky behaviors and encourage academic and extracurricular activities in preparation for college.

Findings reflect that the different values of each religion may facilitate varying trajectories. For example, Sectarian Protestants tend to value family rearing and place less emphasis on pursuing an advanced degree while Catholics have created school systems fostering close-knit religious communities that pave the road for students to attend college. And those raised unaffiliated might have fewer social supports encouraging higher education than those who are part of a religious community.

Immersion into a religious environment in youth paves the way for education trajectories, but in the United States, it’s less clear what happens to religious views once students get to college. Do young adults abandon their religious practices and beliefs during college, even if they grew up in religious communities that encouraged them to become more educated?

Untangling the relationship between education and religion

The best way to research how religion influences education, and vice versa, is to study the same people over time, from before and after they completed their studies. The MRC research team set out to illuminate the complicated relationship between education and religion using data from the 1997 National Longitudinal Study of Youth (NLSY97), which first surveyed youth aged 13–17 in 1997 and re-interviewed them periodically. By 2017, the NLSY97 participants were in their 30s, which means most had already completed all their education.

The researchers assess both the impact of the adolescents’ religious environment on their likelihood of completing high school and the changes in religiosity between those who attended college and those who did not. The first analysis, Model 1, focuses on the impact of religious social networks and support on education, and the second analysis, Model 2, focuses on the impact of college education on subsequent religiosity.

In order to analyze how adolescents’ religious environment impacts meeting college prerequisites, Model 1 features measures from the baseline NLSY97 survey as the independent variables and high school completion by age 20 as the outcome. Multiple measures of the youth’s religiosity are the outcomes of Model 2, which captures the longitudinal trend over time using the measure of educational attainment at specific times to predict their subsequent religiosity.

An important aspect of the MRC project is recognizing multiple dimensions of religiosity, such as beliefs and values in addition to identity, public, and private religious practices. Some aspects of religiosity are more personal, while others are more social, and each may change in different ways over a person’s life.

For measuring change in religiosity as part of Model 2, the researchers used seven individual measures: whether the respondent attends church monthly, prays weekly, believes religious teachings are to be obeyed exactly as written, believes they need religion for good values, believes God has something to do with what happens to them personally, asks God’s help in making decisions, and whether they disaffiliated from their parent’s religion.

They also combine all of the measures except for religious disaffiliation, to identify overall religiosity. Measuring multiple dimensions of religiosity is important because the subsequent declines in religiosity associated with completing college are not the same among different religious indicators and traditions.

Community keeps religion alive

Results from Model 1 highlight religious social network factors as important predictors of high school completion. Respondents who attend parochial school or who have a majority of church-going peers are 92.8% and 56.2% more likely to graduate from high school, respectively. On the other hand, the religiosity of respondents’ parents had little impact on their high school completion rates compared to religious community support and monitoring.

The results also identified persistent differences between religious traditions. Sectarian Protestants are 27.5% less likely to graduate from high school while the Unaffiliated are 33% less likely to graduate than Moderate Protestants.

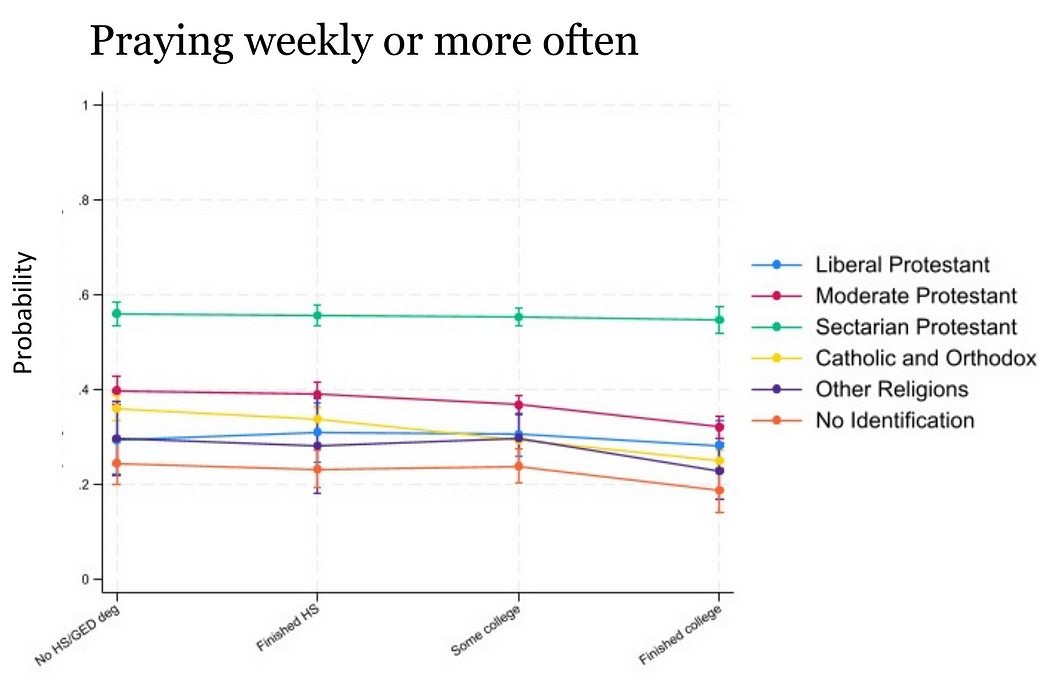

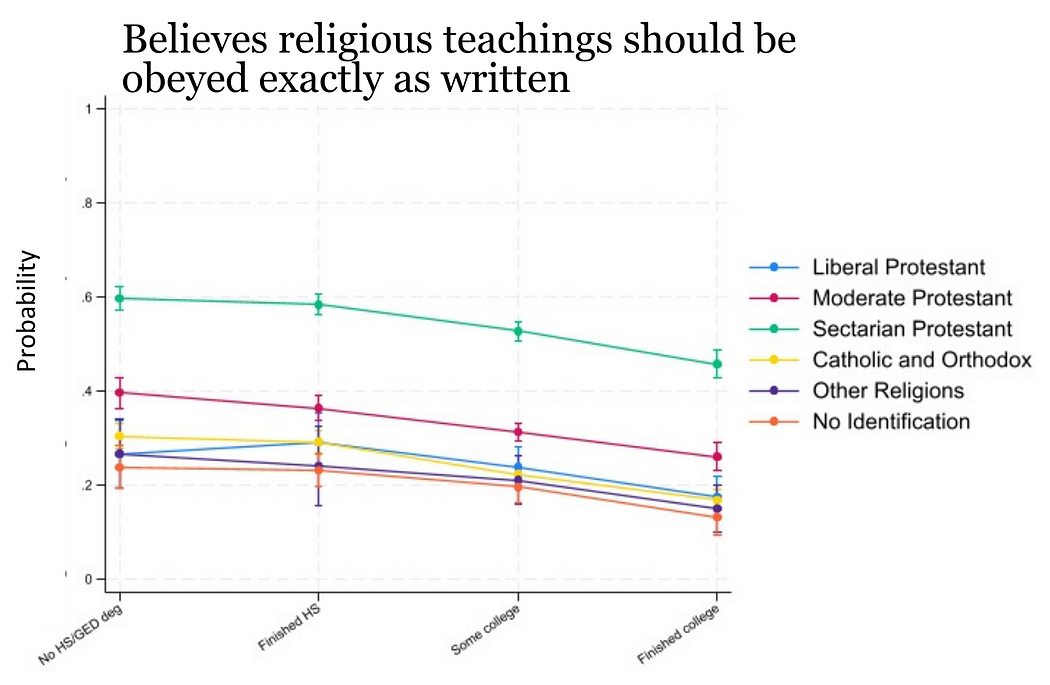

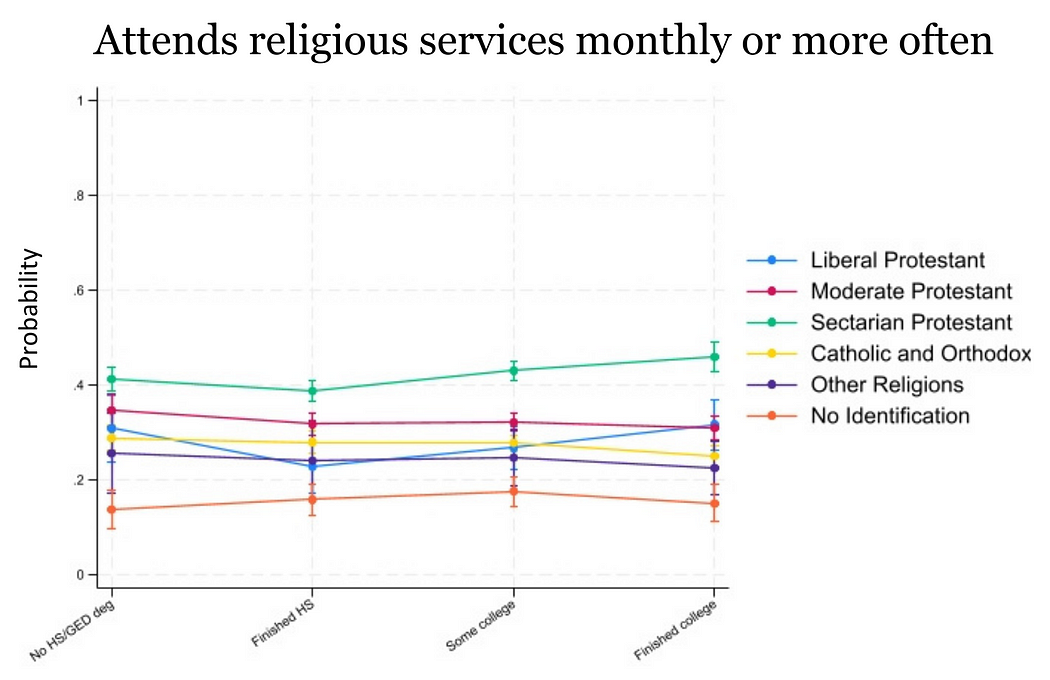

Turning to Model 2, the results suggest the attainment of higher education is associated with a decline in some of the personal religious practices and beliefs. This is the case for weekly prayer, obeying religious teachings as written, associating religion with good values, and asking for God’s help in decision-making. The more public dimensions of religiosity — such as attending church monthly and maintaining a religious affiliation — remain consistent for those who attend and complete college.

Attaining a higher education does not mean individuals will abandon the religion they grew up in or stop showing up to church. While private religious practices and values weaken with higher education, the public forms persist.

This relationship further highlights the significance of community and social benefits that encourage the pursuit of higher education in the first place. And education probably continues to encourage engagement in those religious social circles as opposed to directly undermining all aspects of religiosity.

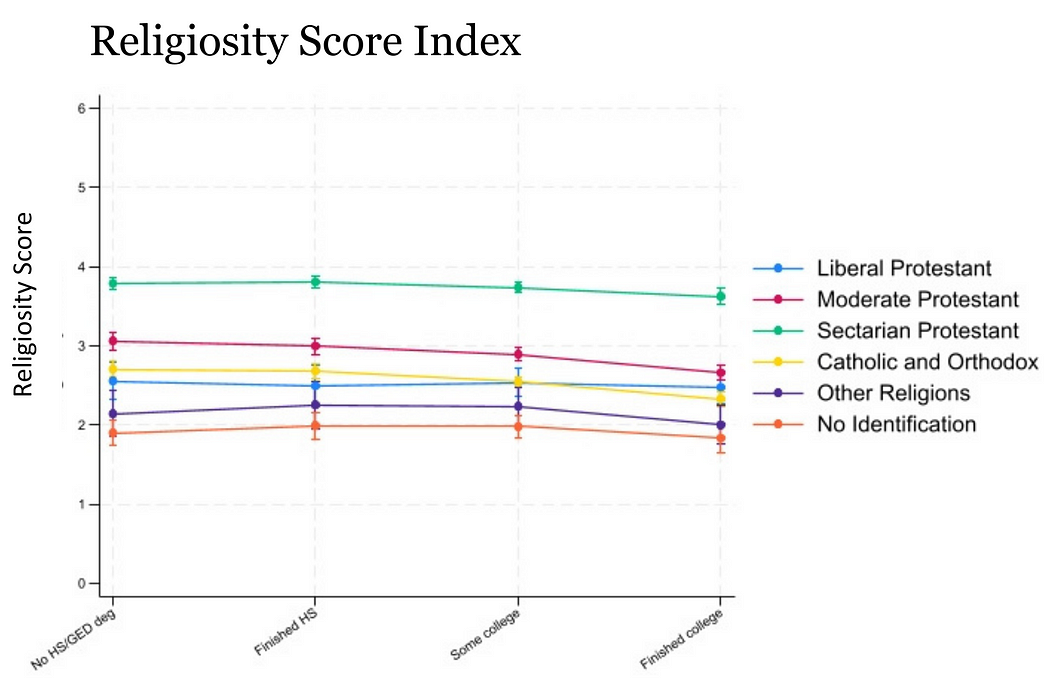

As outlined in Model 2, these changes in religiosity vary by both religious tradition and religiosity measure. The researchers graphed the results to highlight these differences. Selected graphed results from Model 2 are below.

The overall religiosity score, which combines all of the other outcomes except disaffiliation, decreases slightly upon entering and completing college, and the decline is most apparent among those raised as Moderate Protestants or Catholic/Orthodox.

Overall, completing college is associated with a 43.7% decline in respondents praying weekly. Among Sectarian Protestants, however, frequent prayer is just as likely after college as beforehand.

Evident here is the most obvious decline in religious practice among all traditions with college completion leading to a 70% decline in the probability of believing the scripture should be interpreted literally. This confirms that education can loosen rigid religious interpretations, even among those raised in strict traditions.

Attending and finishing college is not associated with a lower likelihood of attending religious services monthly. Notice that finishing college is even associated with an increase in attending monthly worship services for Sectarian Protestants. Since advanced degrees are less common among this group, respondents who obtain higher education may experience increased status within their religious community and be expected to take on more responsibilities in their congregation.

Religion remains resilient

While declining individual practices such as frequent prayer and holding literal interpretations of religious beliefs appear to get chipped away through the attainment of higher education among some religious traditions, the same cannot be said for the public aspects of religiosity.

The impact of religious social networks on completing high school, the consistency in churchgoing through college, and the evidence that respondents do not disaffiliate from their religion indicate that the social aspect of religion remains significant for most affiliations before, during, and after the attainment of a college education. Such a relationship is consistent with other findings that show student participation on college campuses remains significant and college tends to increase religious liberalization.

So, is attaining a college education a matter of secularizing perspectives with exposure to various worldviews or a matter of liberalizing religious views? Some of both are likely happening, but as the MRC researchers have demonstrated, it is a nuanced relationship varying by both religious traditions and religion indicators.