In recent decades, women are participating in the labor force in higher numbers, working longer hours, and pursuing higher levels of education. New laws, protections, and policies have been instituted locally and nationally to make workplaces more equitable. While longer family leave laws have been put into place, women are more often taking longer leaves, resulting in a more difficult transition when they do return to work.

This is just one example of how the real-world effects of policies can vary from what policymakers intended. There are several aspects of equal pay laws and other policies across the US, in Europe, and the UK that have proven effective in narrowing the gender pay gap, while others come up short.

With the rise of COVID-19, it is almost impossible to foresee what the future will hold in terms of gender equality in the workplace. The pandemic has called for more flexible family leave for caregivers supervising remote learning children and caring for sick family members. In December 2020 alone, women lost 156,000 jobs, while men gained 16,000.

US policies

State wage transparency laws protect the worker by giving them an understanding of how much their colleagues are making compared to themselves. These laws have several applications, such as including salary information on job listings, preventing employers from firing employees for discussing their salaries, and requiring salary information to be available within the organization.

The Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor provides data on public wage information by state. States with high levels of protection include California, Colorado, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Oregon, and much of the Northeast (Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, and Vermont). In 2021, a new California law went into effect, analyzing demographics of the workplace based on required reporting on the number of employees, race, gender, job category, and salary.

Wage history bans are an element of equal pay laws in some progressive states that have yielded positive results. A 2020 California court case, Rizo v Yovino, decided that prior rates of pay could not be considered a “factor other than sex” exception to equal pay laws, because previous wages could be perpetuating historical pay discrimination. In addition, a paper published by Boston University School of Law in June 2020 concluded that the wage gap for “job changing women” nearly disappears when there is a salary history ban in place. There is evidence that wage history bans narrow wage gaps in other demographics as well.

Maternity leave policies are some of the most discussed aspects of the wage gap in popular culture. The national policy (12 weeks of unpaid job protection) is often criticized as not being enough support for women and families. Many activists have called for a change of language and extension of the policy to include fathers under a family leave policy. California expanded family leave in 2004, but even those expansions have been criticized.

A study sponsored by the Department of the Treasury analyzes the California act with IRS Tax data (Bailey, Byker, Patel, Ramnath). The analysis suggests that there were statistically large declines in wages and employment for new mothers, but longer leave may encourage women to invest more in their families and less in their careers. A national paid maternity leave policy alongside affordable and safe daycare options would give women more opportunity and flexibility to pursue career opportunities.

An element of this discussion that is underrated or, perhaps, less glamorous, is the impact of part-time work on women’s wage equality. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2019 the total number (in thousands) of employed part-time workers in the US was 26,941 and the total number (in thousands) of employed full-time workers was 130,597. Women made up 64% of part-time workers, and 73.82% of those women were over 25 years old. In contrast, women only made up 43% of the full-time workers.

Most of the benefits helping women in the workforce only apply to full-time employees. Federally, part-time employees are only eligible for job-protected maternity leave if they work 175 non-consecutive days. While there are many reasons why a woman might work part-time, family life is cited as one of the most common factors. Data as far back as the 1990s shows that part-time work as a barrier to equal wages is not a new concept. Websites like MotherWorks have compiled resources for mothers looking for companies that provide benefits to part-time employees. States like Utah, which has one of the widest wage gaps in the country, have a high percentage of women in part-time work.

European and UK policies

While Scandinavian countries appear to be leading the way in gender equality, their progressive policies stop short of reaching representation. Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden) have adopted gender equality policies to eliminate the gender wage gap. These policies include longer paid parental leave for both mothers and fathers, higher wages, and increasing labor participation rates of women.

Social policies have created economic opportunities for women and economic freedoms, but they have not solved gender gaps within the workplace. While these countries have narrowed the wage gap, specifically in corresponding positions for men and women, it has not eliminated the glass ceiling. Women are still left out of authority positions, including CEOs or board members. Scholars think this occurs because women are penalized for longer paid maternity leave with less paid work time, putting them in positions that look less experienced than male candidates. This particular scenario results in women being pushed into certain positions within the public sector but discriminated against within the private sector.

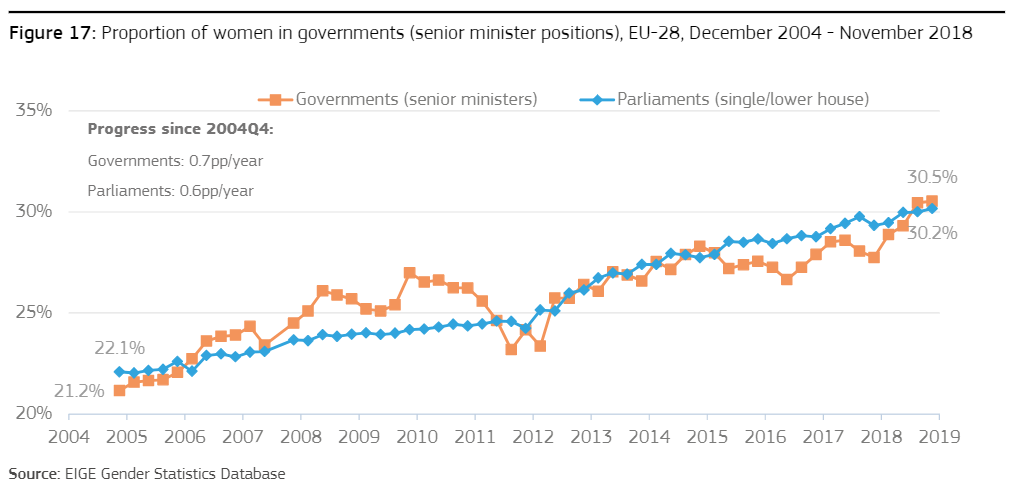

Legislatures with mandatory gender quotas have seen more progress than those that have adopted advisory quotas. Gender quotas require companies or industries to have a certain ratio of men to women, at the executive level, on the board, and/or within the entity. Advisory quotas encourage companies and industries to meet certain ratios but do not enforce them.

Australia is a good example of the success of mandatory gender quotas. The APL party in Australia adopted mandatory gender quotas and was able to match the target, but the Liberal party adopted an advisory quota and has yet to see an increase in women representation. The APL party is significantly farther ahead with gender equality than the liberal party by adopting mandatory quotas.

New legislation including equality for all genders has also been shown to improve gender representation in governments. Slovene legislation saw an increase in gender representation policies after countries such as France and Belgium adopted policies. They adopted gender quotas and created a fast-tracked approach to gender representation in almost all levels of government. With the existing gender quotas from EU countries, mandatory quotas seem to be more effective than advisory quotas at balancing the representation of men and women within all branches and levels of government.

Throughout Europe, countries have adopted gender quota policies for corporate boards. In countries with mandatory gender quotas, there was an increase in the number of women on corporate boards, and most companies met the quota. These mandatory quotas were enforced through fines and time frames. Successful countries include Italy, Spain, Belgium, and France. The UK adopted an advisory quota for public corporate boards. This was not as successful because the loophole allowed firms to switch from public to private to avoid gender quotas without consequence.

The primary drawback to gender quotas is they do not create diversity in all levels of the workplace. It is no more likely for a female CEO to be elected with gender parity on corporate boards, or for representation to be of similar parity within different areas of the firm. One way to enforce gender quotas within companies is to base public funding on gender parity. Gender-based funding was one way this was accomplished. Public funding would only be provided to institutions if women were members of the board or a gender quota was reached.

CMAC research assistants Talia Smith and Sarah Berkowitz have researched wage inequities across racial and gender lines and across regions and vocational settings in the U.S. and Europe. These are Talia and Sarah’s insights and recommendations for future research and policy opportunities.

Sarah Berkowitz

Sarah is an undergraduate student majoring in International Studies at American University with a minor in Arabic. She is passionate about global health, environmental sustainability, and social justice issues. In her free time she likes to read, travel, and volunteer with community organizations.

Talia Smith

Talia is the host/ co-producer of Once Upon a Time: A Storytelling Podcast. She is currently a graduate student at The George Washington University studying Museum Education.