To many, the idea of an invisible person who watches over you and rewards or punishes you according to your behavior sounds like a fairy tale. Sure, many American children believe in Santa Claus, but they eventually outgrow those beliefs. Why don’t people outgrow similar beliefs in a God or gods?

Many beliefs involving supernatural agents are not value-neutral: these beliefs compel people to affirm certain moral values and act in accord with those values. Religious people are deeply committed to gods, ancestors, and other supernatural agents, devoting their time, money, and energy to their service. Religious people organize much of their social lives around religion, are careful to ensure their children acquire the same beliefs, and frequently distrust people who don’t share their beliefs. Why are beliefs in supernatural agents often connected with systems of ethics and identity?

Some researchers point to the connection between belief and ritual to explain why belief in supernatural agents persisted and came to be taken so seriously. This research explores the particularly religious character of belief in supernatural agents.

The evolution of religious ritual

In religions around the world, belief in supernatural beings is expressed concretely through rituals: personal prayers, public festivals, and sacrifices, which can be time-consuming and expensive. Many religious traditions enforce moral and behavioral norms through reference to powerful gods who monitor human behavior.

How did supernatural agents come to be associated with complex, interconnected systems of belief, morals, ritual, and culture — in other words, with religion?

Scholars pursuing an anthropological approach to the origin of religion have focused intensely on the role of religious practices in human societies. How could the normal functioning of ancient human societies lead to the emergence of religion-like systems of interconnected beliefs, ritual practices, and norms? These scholars draw from archeological evidence to piece together a picture of early human and hominin societies.

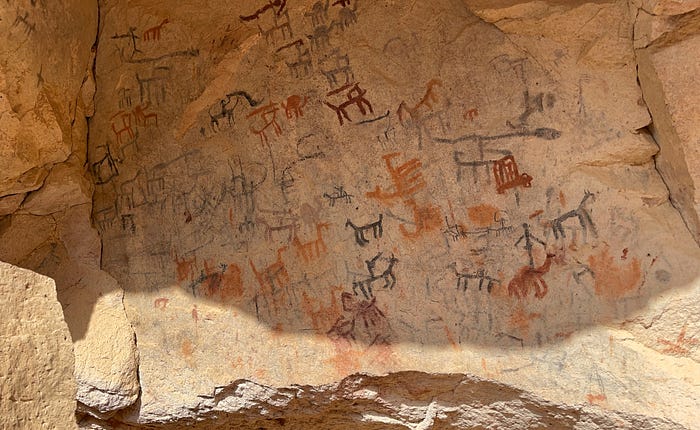

Cave paintings and rock art provide concrete evidence of just how ancient the origins of religion may be. Around the world, artists depicted supernatural agents, such as therianthropes (human-animal hybrids) and larger-than-life figures towering over smaller human figures. The oldest of these figures date from around 30,000 years ago.

Supernatural agents may have appeared in the visionary dreams of the shamans who painted these images. The Lascaux caves include an image which appears to depict a bison appearing in the dream of a shaman whose bodily condition suggests he may be in a stage of REM sleep, when vivid dreams are more common.

Tens of thousands of years ago, humans were sharing their dreams with each other, collectively interpreting their meanings, and taking their implications very seriously. They asked shamans how to understand and interpret these dreams, and dreams featuring supernatural agents could have been generative of new rituals or religious ideas.

Phases of the evolution of religious ritual

Religion likely arose as a response to human societies growing ever larger and more complex over the past 500,000 years. As this complexity increased, the role of rituals as methods for stabilizing social bonds became increasingly vital. Kim Sterelny lays out several phases of the cultural evolution of religion as we know it:

- Embodied religion: initial changes in hominin social structure prompted the evolution of new methods for strengthening collective bonds, such as musicality, song, and dance. This sensitivity to and use of shared rhythmical movement and sound served as the deep roots for religious ritual.

- Articulated religion: as new social identities emerged, norms of behavior and exchange became necessary to lessen the friction between reciprocal cooperating groups. The establishment of these rituals deepened group identity and set norms for life in the group. Affirming belief in these narratives became a signal of loyalty to the group.

- Ideological religion: some groups elaborated these rituals and narratives by tying them to the group’s morals. At this point, believing in the rituals and narrative became compulsory, since it goes hand-in-hand with affirming and following the norms and morals of the group. Ideological religion arises when ordinary narratives, explanations, and beliefs are universally (or nearly universally) affirmed, thereby taking on distinctive social and emotional roles.

Credibility-enhancing displays

But why would involvement in religious rituals “prove” commitment to the group? Why would these actions “speak louder than words” or other actions?

Joseph Henrich, who studies culture-driven genetic evolution, argues that religious rituals act as “credibility-enhancing displays” (CREDs). These are costly actions, taken consistently with one’s stated beliefs and observed by other community members. CREDs increase the credibility and trustworthiness of the actor and demonstrate the genuineness of their belief.

Knowing whom you can trust is vitally important today and would have been especially critical for early humans. According to Henrich, humans developed a cognitive bias to favor and trust people whose actions, especially when they are costly, align with their words. This cognitive tendency to trust people who perform CREDs catalyzes the emergence at the cultural level of self-stabilizing, interlocking sets of beliefs and concomitant costly practices. In many instances, CREDs became ritualized and routinized, such as sacrificing one’s produce or animals for a communal meal or participating in an exuberant ritual dance that enacts a religiously significant narrative.

Whether ritualized or not, CREDs function as a reliable signal of trustworthiness, ultimately promoting cooperation within and between human groups. CREDs simultaneously boost the credibility of the actor and reinforce the plausibility of the beliefs that guide those actions.

Religious beliefs about supernatural agents that seemingly lack direct empirical support gain indirect support through the CREDs of community members. Especially for impressionable children, observing respected adults performing actions that presume the reality of gods or other supernatural agents deepens belief in those beings.

The bigger picture

In our companion article, we explored theories on the origin of belief in supernatural agents. These theories were developed by researchers in the cognitive science of religion, which seeks to explain religious belief in terms of natural human cognition. The theory of the “hyperactive agency-detection device,” or HADD, explains why humans tend to assign agency to random or unexpected occurrences. The theory of minimally counterintuitive concepts draws from the fact that such concepts are more memorable to explain how supernatural agent concepts might have been more likely to be passed on through generations and spread within and across cultures.

Through a process of gradual cognitive evolution and cultural competition, religion emerged.

Humans’ tendency to attribute agency due to HADD and dream experiences created the first supernatural agent ideas. The ideas of these supernatural agents survived because they were minimally counterintuitive and easily passed down in stories. Rituals and CREDs — necessary for the smooth functioning of increasingly complex human societies — reified certain narratives and beliefs involving supernatural agents.

The origin of supernatural agent concepts — and continued belief in and commitment to these beliefs — is a complex process that sheds light on humankind’s first attempts to explain the world.

Jessie Saeli

Jessie is a student in the M.A. program in philosophy at Boston College. She began her graduate studies after graduating magna cum laude from the University of Notre Dame, where she studied philosophy and Russian. Her primary interests are existentialism, Russian philosophy, and the question of what a “self” is. She enjoys reading and writing about philosophy, theology, and literature.