Many American girls have been taught to consider their wedding day the “happiest day of their life.” But how do we reconcile that sense of hope with the fact that entering into an intimate relationship with a man is one of the leading risk factors for gendered violence? Women are more likely to be raped, injured, or killed by their current or former intimate partner than by any other person.

Researchers in CMAC’s Sex Differences Project (SDP) are working to understand some of the sociological factors that lead to both increased risk and potential protection from domestic violence. Through an extensive cross-cultural study, they found that the prevalence of specific types of religious rituals—especially rituals that fostered solidarity among women and community, female initiation ceremonies, and the presense of female shamans—seems to actually help protect women against domestic violence.

Before jumping into why or how rituals generate protection against violence, let’s first take a look at the fraught relationship between marriage and domestic violence. Anthropologist Judith K. Brown notes that the excitement that we typically associate with weddings is far from universal. She explains in some cultures “the tears mothers shed at the weddings of their daughters are tears of true grief because their daughters will be separated from them and will embark on a life of toil, possible abuse, and the dangers of child-bearing under traditional conditions.” Similarly, among the Yanomamo of the Amazon rain forest, women’s fear of marriage appears to be somewhat proportional to the distance away from her family’s village—the further they are away, the less likely their brothers will be able to protect them from a cruel and violent husband.

Misogyny and antagonism toward women are incredibly complex phenomena that vary and morph depending on things like economics, social norms, and gender roles. But cross-cultural comparisons can help us make sense of some of those broader cultural factors.

For example, SDP researchers found that societies in which women’s bodies and menstrual cycles are viewed with shame or disgust have higher levels of spousal violence. Likewise, when women are excluded from elaborate male-only rituals it appears that domestic violence increases.

Such societies tend to have similar norms around where and how a couple lives after they get married. Namely, they tend to have what anthropologists call patrilocal marriage residence patterns. This means that when a couple gets married, the woman must leave her family, friends, and social network to go live with the man’s family; about 67% of cultures historically and worldwide are patrilocal.

Therefore, when SDP researchers began exploring the societal factors affecting the prevalence of domestic violence, marriage residence patterns took center stage. Using the Sex Differences and Religion Database (SDRD), a large cross-cultural dataset constructed by the SDP and consisting of 268 variables for 215 cultures, the researchers verified that, indeed, in societies that are patrilocal, domestic violence levels were significantly higher than when men were the ones to leave their families of origin to join their in-laws (matrilocal societies).

This particular finding is, unfortunately, not too surprising. When women leave their social support systems behind they are reliant upon relative strangers for protection, solidarity, and security. Anyone who has moved to a new town knows that it can be a significant challenge to make new friends and to find a place in a new social structure. For many people, one of their first tasks will be to find and join a religious community. Why?

Because, as the SDP researchers and many prominent anthropologists argue, religious communities are one way that people create fictive kin networks—essentially, networks of people who are not biological family, but who behave and feel as though they have a familial relationship.

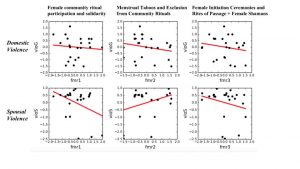

With this in mind, the researchers next looked into the relationship between female-specific ritual participation and levels of domestic violence. The idea is that the female-centered rituals promote bonding and solidarity among women, which in turn, may have a protective effect against the high levels of domestic violence women in patrilocal cultures face.

And indeed, this is exactly what they found: cultures that present more opportunities for certain types of women-centered rituals have lower levels of domestic violence. This finding is strong support for the idea that rituals are really important bonding strategies for women who must create new support structures or fictive kin networks. The payoff is dramatic and clear: a potential decrease in the risk of domestic violence. More research is certainly warranted for such an important finding.

For any inquiries or comments, please email admin@mindandculture.org.