In 2017, CMAC Researchers Jonathan Morgan, Connor Wood, and Catherine Caldwell-Harris published their paper “Reflective Thought, Religious Belief, and the Social Foundations Hypothesis” as a chapter in the book The New Reflectionism edited by Gordon Pennycook. In 2021, AI bots on academia.edu scrutinized CMAC Executive Director Wesley Wildman’s recent download history and inferred he might be interested in the same paper. In a world where AI is supposed to be better than us at making connections and suggestions, it’s ironic when it can’t anticipate existing (real-life) social networks.

The paper addresses a new topic that seized people’s imagination in the past decade: Are people with a preference for intuitive thinking predisposed to find religion appealing, while those with a preference for logic resist that, and find a purely materialistic world most convincing?

Jonathan Morgan

Jonathan is a Postdoctoral Fellow at CMAC. He has studied religion, theology, and psychology. His research focuses on understanding spirituality and its relationship to mental health.

Connor Wood

Connor is a Research Associate at CMAC. His research interests include religion and ideology, self-regulation, the evolution of social hierarchy, and the origins and functions of music.

Jonathan and Connor have worked on CMAC’s Cognitive Styles and Religious Attitudes Project, which is closely related. A lot of the new research on cognitive style and religion was coming out of social and cognitive psychology.

They felt that something was missing and wanted to bring religious studies into the conversation.

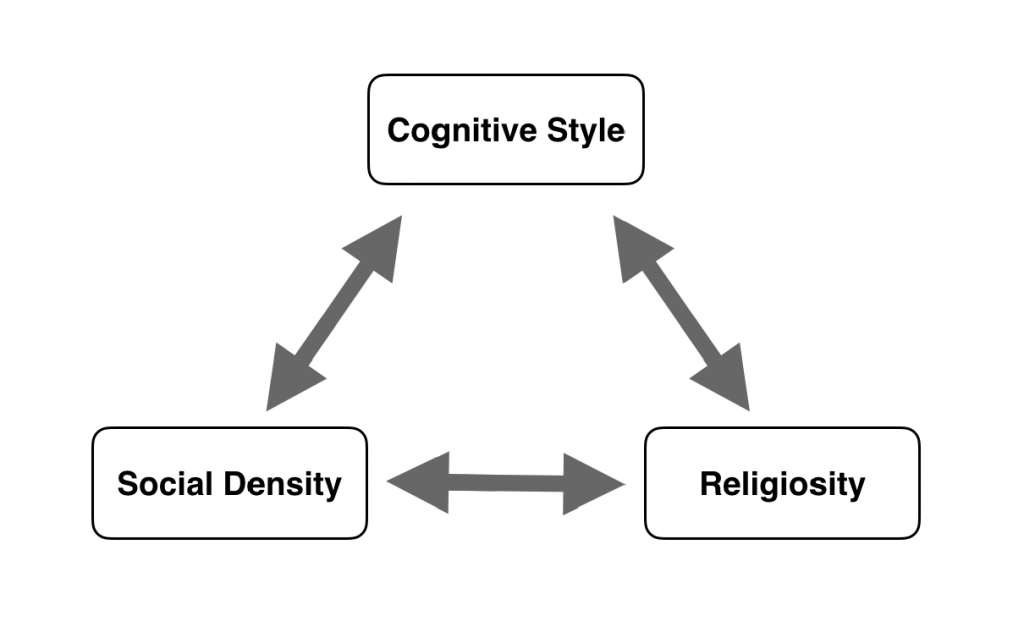

Connor believed that the social aspects of religion were playing a greater role in linking religious belief with cognitive style than many people recognized. “Religion was often seen as something that just naturally emerged out of individual brains thanks to automatic cognitive biases such as anthropomorphism. But a century and a half’s worth of theoretical work in religious studies shows that religion is “eminently social,” in Émile Durkheim’s words.”

For Catherine, the relationship between personality and religious belief was what drew her to the topic. “For most of human history, religious belief and religious adherence veered towards 100%. Obviously analytically-minded people existed. They embraced religion like everyone else of their era, Isaac Newton included. Therefore, the North American correlations between reflective thinking and atheism (or nonbelief) are likely restricted to present day North America.”

Catherine proposed that only in an environment where atheism/nonbelief was socially accepted would personality traits have a role for influencing religiosity. Along with social acceptability of atheism, venues for learning about atheism would need to exist, such as books and role models (the ‘constraining environments hypothesis’).

Since the paper was published in 2017, the researchers have continued to study these questions, including a study on religiosity and cognitive style in Turkey. Catherine says of the study, “I measured intuitive vs. cognitive style and found it was mostly unrelated to religious belief. Instead, exposure to English (and western secular ideas) was a route for decreased religiosity.”

Catherine and Jonathan had previously worked with Gordon Pennycook, who is one of the key advocates of the idea that analytical thinking could influence rejection of religion. Pennycook’s goal was to continue the intellectual work begun by Kahneman’s bestseller, Thinking Fast and Slow, and examine how thinking styles influenced large domains like human morality, creativity, the paranormal, and conspiratorial thinking.

Pennycook thought the CMAC team could provide a unique and diverse cross-cultural perspective on the intersection of personality styles and religious belief. After all, Catherine is psychologist and has previously published a theoretical paper and an empirical paper on atheism, while Connor and Jonathan both have a background in religious studies tradition, with expertise on culturally diverse religious traditions.

This paved the way for Jonathan, Connor, and Catherine to publish their chapter in The New Reflectionism. The chapter provides a novel theory to explain the association between preferences for reflective cognition and irreligiosity. Most other theories suggest that reflective thinking overrides some of the intuitive biases that foster religious beliefs. Drawing from research in anthropology, sociology, and psychology, the researchers offer an alternative explanation– that religious belief is a form of socially motivated cognition.

The book Thinking Fast and Slow, which was a source of inspiration for Pennycook in editing The New Reflectionism, was a popularization of an idea that had been gaining momentum in psychology for the prior decade: dual process theory. Dual process theory is the idea that there are two ways to process information. One, intuition, is really fast and largely heuristic. The other, reflection, is slower and more deliberately considers the information at hand.

Motivated cognition is the idea that various goals or needs can shape how we process information. In this context, the goal of maintaining affiliation with one’s religious community likely bears a strong influence on how people relate to information that is relevant to their religious beliefs.

Since The New Reflectionism was published, the well-known 2012 Gervais paper fell victim, at least in part, to the replication crisis that’s been happening in psychology. However, the 2017 Sanchez paper that tried to replicate the Gervais paper had its own flaws. Jonathan points out that the title of the article, “No evidence that analytic thinking decreases religious belief,” was misleading. Sanchez et al. only failed to replicate the third experimental manipulation.

Jonathan says, “That was where Gervais and and Norenzayan tried to prime analytical thought with a picture of Rodin’s Thinker. So, that specific manipulation didn’t work. But it was the weakest experiment of the three experiments in Gervais and Norenzayan 2012. The authors should have chosen the strongest example to replicate.”

And other research, including a meta-analysis lead authored by Pennycook in 2016, has consistently found a modest but reliable correlation between atheism and reflective (System 2) thinking.

The CMAC researchers’ 2017 paper is a way for readers to appreciate how complex religious beliefs are. According to Jonathan, “They’re not just propositional statements about the way the world is, they’re also important parts of people’s identity and ways to show what communities we appreciate. Hopefully this added complexity helps remedy the tendency to view such beliefs as irrational.”

Papers mentioned:

Morgan, J., Wood, C., & Caldwell-Harris, C.L. (2017). Reflective thought, religious belief, and the social foundations hypothesis. In G. Pennycook (Ed.), The new reflectionism in cognitive psychology: Why reason matters (pp 16-38). Abingdon: Routledge.

Caldwell-Harris, C.L., Hocaoğlub, S., & Morgan, J.R. (2020). Do social constraints inhibit analytical atheism? Cognitive style and religiosity in Turkey. The Journal of Cognition and Culture. 20(1-2), 1-21.

Gervais, W. M., & Norenzayan, A. (2012). Analytic thinking promotes religious disbelief. Science, 336(6080), 493-496.

Sanchez, C., Sundermeier, B., Gray, K., & Calin-Jageman, R. J. (2017). Direct replication of Gervais & Norenzayan (2012): No evidence that analytic thinking decreases religious belief. PLoS One, 12(2), e0172636.

Pennycook, G., Ross, R. M., Koehler, D. J., & Fugelsang, J. A. (2016). Atheists and Agnostics Are More Reflective than Religious Believers: Four Empirical Studies and a Meta-Analysis. PloS One, 11(4), e0153039.

More from these researchers:

Caldwell-Harris, C.L. (2012). Understanding atheism/non-belief as an expected individual-differences variable. Religion, Brain & Behavior, 2, 4-23.

Caldwell-Harris, C.L., Wilson, A., LoTempio, E., & Beit-Hallahmi, B. (2011). Exploring the atheist personality: Well-being, awe, and magical thinking in atheists, Buddhists, and Christians. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14, 659-672.