There are many connections to be uncovered at the intersection of academia, scientific data, and 21st century communications. When sharing our research, we aim to employ culturally competent communications. This is crucial when it comes to communicating the complicated and nuanced social issues we address, such as vaccine hesitancy.

At CMAC, we take an interdisciplinary approach to everything that we do, and that includes applying concepts from our research to how we talk about it.

Culturally competent communication means using methods to reach your listener that resonate with them. It takes into account the background that they are coming from and the point of view that they might be carrying. This is something we do all the time; the way you speak to your boss is different from the way you speak to your mother, which is different from the way you speak to your best friend. When we communicate with each individual, we quickly assess their background and our relationship, and we choose our diction and method based on that assessment.

However, when communicating complex social issues, this assessment must take place on a larger scale. You must understand the entire population that you are reaching, and within that population the smaller cultural pockets. To do so requires an interdisciplinary approach, using anthropology, sociology, and even an understanding of religion and values, as a lens to better understand communications, information processing, and human behavior.

By combining historical context, real data, and lived experience, we can better understand human behavior. Creating effective public health policies requires understanding specific populations or cultures, and how they will respond. Each individual has their own set of experiences that alter their perspective, maybe personal fears and doubts, personal experiences that reinforce historic lessons, or even language background that might shift the way they deduce meaning from word choice. But we can identify patterns.

CMAC’s work falls into what we call the mind-culture nexus: the area where societal, lived experiences, practices, and beliefs intersect with the psychological and neurological aspect of their decision-making process. We cannot ignore this when we are investigating complex social issues. We must understand that people do not always act logically and their decisions cannot always be quantified into one area of study. It’s complicated.

This is all the more relevant when investigating vaccine hesitancy. The risk of severe illness or death from Covid-19 has now been mitigated through vaccines, and the possibility to resume normal life would lead us to assume that choosing to be vaccinated is the most logical choice.

However, for some people that is not the case. Some may have heard firsthand stories of family members who had a bad reaction to a vaccine, some may not have an existing relationship with a medical practitioner who can answer their questions, some may not have health insurance and worry about the associated costs, and some may be untangling online conspiracy theories and disinformation campaigns. These are just a few examples of reasons people are hesitant to get vaccinated against Covid-19.

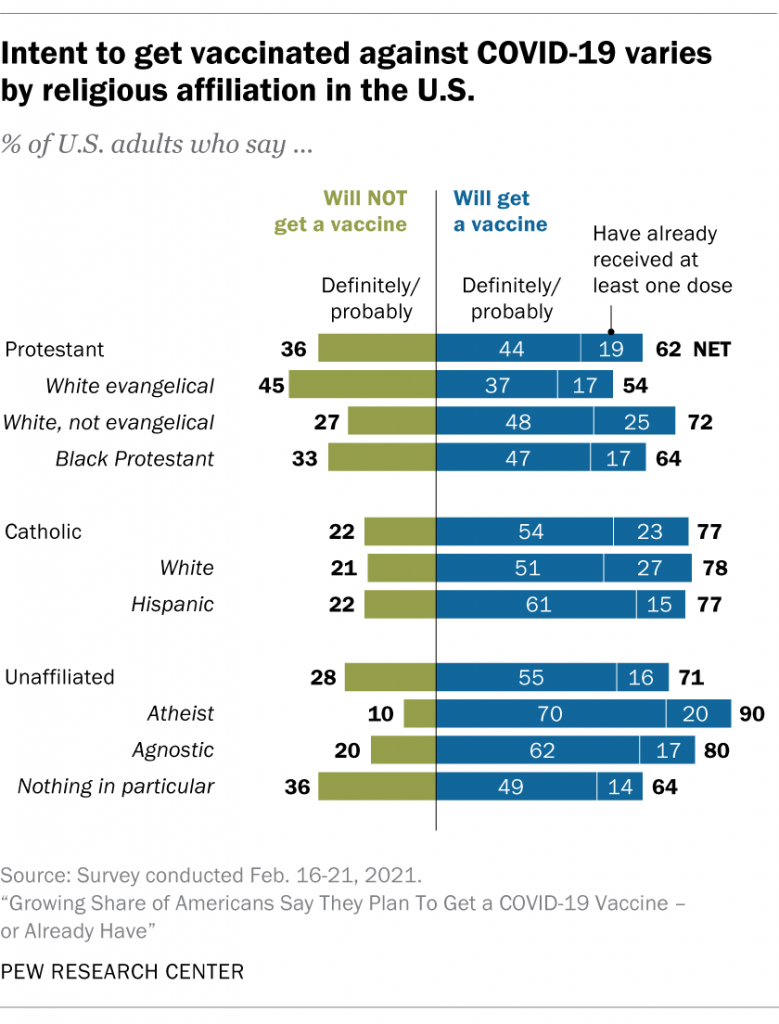

Anthropology teaches us how to look beyond the surface of the data. If surveys tell us that roughly 30% of Americans are vaccine hesitant, that information is not enough.

We need to understand that that percentage contains nuances. Within the larger group, there are many segments that will each respond differently to the same messages.

Some might be hesitant because they believe the vaccine goes against their religion, or they are not at all hesitant but are still unable to get easy access, or that they might be willing to be vaccinated once they hear from a friendly face who has already gotten the shot.

Incorporating methods from humanities fields like anthropology allows us to identify the unique concerns of these different groups and build better tools that will address these concerns in an effective way.

These are lessons we see validated by the leading evidence-based research on combating vaccine hesitancy.

At CMAC, we are working to take all of these possibilities into account and tailor our communication effort to the individual communities. This means sharing information that is true and relevant, that gives the entire picture, and that does not blame or isolate. Ultimately, the decision to get vaccinated is a personal one, and our goal is to produce information that assists people in making that decision confidently.

Lila Norris

Lila is an undergraduate student at Boston University studying Socio-Cultural Anthropology. Through her education and internship experiences she has gained a holistic understanding of culture and media. Lila is interested in social justice and work in the nonprofit sector. After her undergraduate studies she intends to pursue a J.D. in hopes to seek policy based solutions to social justice issues.