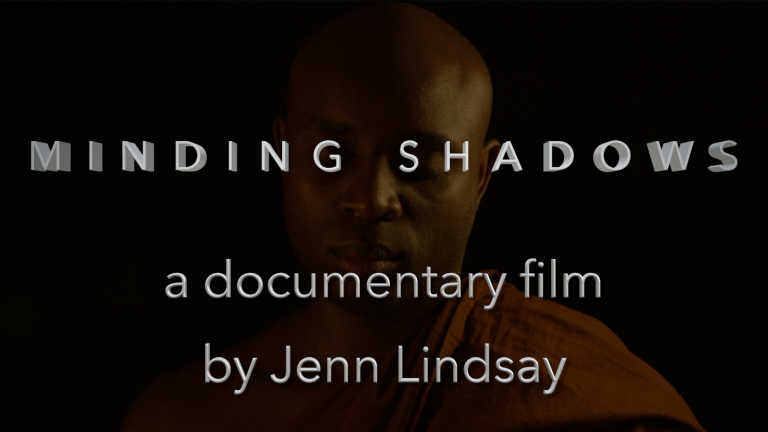

We recently interviewed CMAC alum Jenn Lindsay about her career as a filmmaker and the role that her work with CMAC and IBSCSR played into launching her into her current work. Check out the crowdfunding campaign for her upcoming film Minding Shadows and watch for the second part of this interview, which goes into more depth about the film production process. Note that the campaign ends on July 5 at midnight Pacific Time, so donate now if you are going to!

First, can you say a little bit about what you did at CMAC, your connection with the Institute for the Bio-Cultural Study of Religion (IBCSR), and your background there?

Jenn Lindsay: IBCSR! That’s a blast from the past. When I started my Ph.D. at Boston University in 2011, that was the hub for Wesley [Wildman]’s workings in the scientific study of religion, and I had just finished my master’s down at Union Theological Seminary, which I went into to get out of the cycle of starving artistry. I’d been working in music and film for over a decade, and I was always piecing together a very precarious existence, and starting to feel like I could use a little more structure and some health insurance. So, I decided to take refuge in grad school, which is a great place to get out of the sun and off the job market for a while, and if you’re lucky enough to be a nerd who can think about a Ph.D. then you’ve got that much longer out of the sun.

I made my way through my master’s and then up to Boston, but I still had put years into developing my filmmaking craft and my composition, and I was very confused about these different parts of me and how they fit together. But I thought I’d just have to completely shelve the artistic parts of me for a while.

Then one magical day, I think it must have been 2012 or 13 or so, I was hanging around Wesley, who I tended to follow like a little duckling, because he’s so amazing and such an incredible educator and so warm and so supportive. And he said, “Wait a second. You’re the one that has the visual storytelling background, right? And that’s great, because here I am at the helm of these highly specialized super-tech academic projects, and we always struggle with connecting to a broader general audience and explaining what we’re doing. And you understand the specialized technical stuff, but you also know how to do visual communication to a broader general audience of ‘untutored lay people.’” (That was our joke phrase.)

And he said, “Do you think you could help explain some of the research that we do?” Of course, I was like, “Yes, of course, definitely! What was it? What is it I need to explain again?” So I came into the IBCSR fold as a documentarian to start building animations about the IBCSR research.

I initially started building little mini documentaries, in between 5 and 10 minutes long, about a bunch of different projects going on having to do with social scientific research on spirituality, MRI research on Parkinson’s disease and how that connected to the degradation of spiritual experiences, and a big range of projects.

I guess it was 2015 when a momentous moment happened. Wesley asked me for a Skype meeting. And he said, “Listen, if I could find the money, do you think you could make a full documentary about the application of computer modeling and simulation to the study of religion?” And of course I was like, “Yes, of course, absolutely. I’ve got some ideas.”

And I got up from the meeting and was like, “What’s computer modeling and simulation?” Just not my wheelhouse. So, I started out. They had gotten this massive multimillion dollar grant from [the] John Templeton [Foundation], to start the MRP (the Modeling Religion Project), and Templeton’s very, very savvy with their public communications. They said to us, “We highly recommend a way to communicate this research to the general public.” And I was already there as the helper on that front.

I started filming. I guess their first meeting was in October 2015, and they had 2 meetings a year planned for 3 years, so I thought, “Oh, that’s perfect.” With every meeting there was a slightly different thematic emphasis, and I could make a docuseries about the whole Modeling Religion Project. So that’s what I undertook.

I started developing this docuseries. There were 8 episodes, and something funny happened around… I think it was Episode 3. I showed it to a friend, and she was like “Snooze! This is not interesting to someone who’s not interested in religion or computers, and that’s not everyone.” And I was like, “Right, interesting. I need to think of some universal questions that could draw people in and help the help that make this topic relatable.”

And what is the most relatable amongst all of these topics? Definitely violence, that universal question, very hot in 2015 and 2016. “Am I going to die in a religion-driven terrorist attack? And who’s doing something to stop that?”

I realized that this would probably work better as a feature, documentary revolving around the religious radicalization topic. I am still committed to finishing the docuseries. But I also found out that film festivals require that, if you’re trying to debut a feature documentary film, it can’t be carved out of a series. It has to be a standalone piece. So, I had to finish this feature film before we released the series, and the feature film is finally done 9 years later, and it’s having its world premiere this fall. So, the series can finally be released at some point. It’s been a long way.

And this Simulating Religious Violence documentary, which I filmed from 2015 through 2018, then we were in post-production for a long time. In 2017, I also met the protagonist of my other feature documentary, venerable Sangharakkhita. He was a Rwandan Buddhist monk who had an incredible story about surviving the genocide and going into martial arts to achieve vengeance, then being transformed by the unexpected practices, then having a wild immigration/refugee ride around the world as he was stateless for a long time. It was just an incredible story.

So, I was filming both movies at the same time, and Simulating Religious Violence, since it was attached to this research project, took priority in terms of getting finished. I had finished my Ph.D. in 2018, and at the beginning of 2020 I thought to myself, “Gosh! You know, I have 3 years of footage for the Simulating Religious Violence movie. I’ve got 3 years of footage for Minding Shadows. I don’t know where to turn. How do I move forward? I’m just one person, and I’m starting to adjunct as a professor of Sociology of Religion at John Cabot University.” And I was like, “Wait a minute. I’m a professor like I can pay people in school credit, students in the Communications Department dying to get their hands on a real movie project. OK, I could do this.” So, I put together a team of 5 kids in the spring of 2020. And we basically got through Covid by working on this movie together.

So at some point, I guess it was 2021, one of the kids on the team who was a marketing specialist, said, “Hey, Jenn, you know, instead of releasing these movies when they’re done separately so as to atomize separate projects, why don’t we focus on developing a production company as a vehicle for both of them?” And that’s when my production company So Fare Films was born.

At first, it was just revolving around these two movies. But Simulating Religious Violence has a lot of news footage in it that needed to be licensed and cleared by my lawyer, and that process took about a year-and-a-half. So, we had to make up a lot of other documentary projects related to religious diversity and social diversity, just to give the intern something to do. We ended up building a company with a pretty big catalog out of nothing. Basically, we run on Scotch Tape and gummy bears.

And now here we are finally finished filming Minding Shadows and going through this crowdfunding campaign to fund post-production, and someday that’ll be finished, too, and who knows what the next chapter is like? I started to dream about learning how to play drums or do beekeeping or something. I think I need a break from moviemaking.

Anyhow, CMAC was sort of a launch pad and all the all the different work that I did for the IBCSR movies. So, this was really my laboratory to teach myself how to do this.

You’ve mentioned a lot of different things that you’re doing. And two of the things that you are, and that you do, are you’re a scholar and you’re a filmmaker, right? Could you talk a little bit about how those relate to each other?

Jenn Lindsay: There are a few ways to answer the question. One is very concrete in terms of how filmmaking comes into my classroom. In addition to teaching social science courses, I can also teach filmmaking and practical media courses. So, it’s expanded my teaching palette. And anytime you’re teaching something you’re also strengthening your craft because you’re continuously learning and fine-tuning yourself.

So, it’s been a great feather in my cap in terms of continuing to get stronger as a visual storyteller. But it is also cool to be able to come into my Sociology of Religion course, for example, and say, “Hey, guys, we’re going to talk about how complex the matter of choice is in whether a Muslim woman will bear a hijab or not, what that has to do with her family, her culture, her identity, her level of religious vitality, all that stuff. And, by the way, I have a documentary that I made in Indonesia in 2011 to get us talking about it.”

I have a lot of teaching tools in my Vimeo and YouTube accounts that allow my subjects to speak for themselves rather than me, just droning on and describing things that I’ve done in my research. So, it’s nice to be able to kind of carry my data sets around with me at the click of a URL. I can bring people into somebody’s world with a much more vibrant degree of thick description than you find in a peer-reviewed journal article.

Although, of course, it’s irresponsible not to acknowledge the fact that documentary film, though it’s grounded in nonfiction and the real world, is still a highly mediated art form, and you’re still choosing where to point the camera. Then, you’re editing for narrative, clarity, and engagement. And you’re layering in music. And you’re thinking about character development. So, it is also a very artificial world, a representation of a world, a model. It’s a simulated version of a topic. So, I always try to help my students understand that documentary video footage is not raw data. In that sense, it starts a really useful methodological conversation, too.

I think, also, just on a personal note, having this multi-method approach to collecting data and dealing with human stories is much more professionally satisfying for me. When I’m stuck in just academia-land, I get really angsty really fast about “Who’s this for? What am I doing?” I find it to be incredibly difficult to do good, precise, credible, scholarly work coupled with “Who is ever going to use this or see this? So why am I doing this?” Even if it’s published, it just all seems to fly away into nothingness. Not that my films have a broad audience either yet, but it feels a little bit more concrete, and at least accessible for the broad general audience of “untutored lay people.” So, it keeps me much more creatively satisfied.

I think the academic work world can be dry and with unclear destination. So at least I have two tangents of unclear destination to apply my efforts to rather than just one.

To be continued…