Generative AI has been at the forefront of discussions about the future of almost every field recently. It has the potential to drastically transform how we work and how we think. In many ways, the transformation has already begun. Tools like ChatGPT, Bing, and Bard have gained traction quickly and are developing so rapidly that industry experts and policymakers are unable to keep up.

The first policy of its kind

CMAC co-founder and Executive Director Dr. Wesley J. Wildman has been a leading voice in these conversations. In February, Dr. Wildman tasked his Data, Society, and Ethics class at Boston University with creating a policy for the use of generative AI tools in academic settings. The class had a discussion about how to incorporate generative AI into the curriculum.

Dr. Wildman acknowledged that it was difficult for him to know how to grade assignments when students could be using AI to generate their answers. But additionally, he wanted to have the opportunity to set clear expectations with students about how they could use the technology to assist their learning, without compromising the skills they will need for a future driven by AI.

The most helpful thing for me as the professor has been to listen to the students and they’ve said very clearly ‘We need help to understand how to use generative AI. We don’t want to harm our skillset, we don’t want other people to cheat.’

Wesley Wildman, WHDH

It quickly became clear that a full ban was unreasonable, and it would leave students unprepared for a career after college. Fundamentally, the Generative AI Assistance (GAIA) Policy that his class developed outlines that students should use AI like ChatGPT to automate mundane tasks. Then, they are responsible for thinking critically about the output of AI and building on it to create something novel for their assignments. The policy also gives grading guidelines for faculty, encouraging them to check how much generative AI is present in an assignment and establish a “baseline” for assignments that use tools like ChatGPT.

Within weeks, the policy was adopted by the Faculty of Computing and Data Sciences. BU Today and the Boston Globe reported on this unique approach, which may be the first academic policy to address generative AI in the country. The policy has the potential to be adopted across Boston University, being tweaked based on feedback specific to different schools within the university.

In an interview on The Crux podcast, Dr. Wildman explains that ChatGPT is another tool to train students on. Universities may be tempted to instill an all-out ban, regarding generative AI under the umbrella of plagiarism, but this is unrealistic. It is both hard to detect the use of generative AI and likely to produce false positives in standard plagiarism checks. Dr. Wildman encourages universities to consider what they mean when they talk about educating and training their students. Most professors would allow their students to discuss complex ideas with each other, find resources online, and get a feel for the landscape of the topic before and during coursework. ChatGPT and similar tools can be considered as one avenue for this type of discovery, as long as students can demonstrate how they engaged in critical thinking beyond the output they were given by an AI. Similar to how writing or the printing press revolutionized the way humans think and learn, we all need to be trained on how to think through the lens of generative AI.

I think what we talk about is [it’s] more like the printing press. It’s transforming the way people use objects to extend their cognitive powers beyond their own minds. We’ve become very good at doing that with all sorts of tools—calculators and so on. But the printing press changed the way we think, changed the way we taught each other. It changed everything about education. This is similar in scale.

Wesley Wildman, BU Today

Thinking more broadly than higher education, Dr. Wildman addressed the idea of K-12 policies in this Reddit AMA thread. He says,

“K-12 education critically depends on using writing to help students learn how to think. Since AI text generation is impossible to block, even if you block it on a school network, we might need to reconsider our methods for teaching students how to think. In STEM education, we adapted to the abacus, the slide rule, the arithmetic calculator, the scientific calculator, the graphic calculator, and Mathematics software – we did that by reconsidering pedagogical priorities. AI text generation is a deeper problem, I think, but the same principle applies. If our aim is teaching students how to think, ask how we did that before the printing press. It was largely through orality, from verbal reasoning to environmental observation. There ARE other ways to discharge our scared duty to our students, including teaching them how to think. This is not a POLICY; it is a PROCEDURE. Teachers need to get ahead of this by thinking about their pedagogical goals.”

Ethical concerns

Generative AI is essentially an algorithm with the ability to complete sentences based on statistical probability. A new development called a transformer has allowed AI to become significantly better at replicating human language. These algorithms are trained on massive amounts of data, in order to better predict what words will follow each other.

In an interview with the HealthMatters podcast, Dr. Wildman outlines a few ethical concerns that come up in regards to this data:

- The data has to come from somewhere. While some companies are relatively transparent about where they get their data, we don’t know for the most part. There are also ethical concerns regarding bias, depending on the origins of data.

- Content has to be moderated and the algorithm has to receive feedback about what is correct and helpful. For the most part, this moderation is outsourced to third world countries where labor is much cheaper.

- There is, of course, potential for economic disruption and job displacement.

On The Crux, Dr. Wildman further outlines some of his core concerns about managing AI tools.

- Although the source of data used to train algorithms is potentially an ethical concern, making the data publicly available could be as well. There is potential for great harm, whether intentional or not, when people have access to the large datasets and code that is used in language learning models.

- The criteria for equity, justice, and human wellbeing stay the same as they always have with the invention of new technologies. Keeping the most vulnerable in mind and critically thinking about the unintended consequences needs to be a key consideration for those at the forefront of developing these tools.

- We have a lot to learn about communicating with AI in a way that aligns our goals with the goals of technologies. This is largely a matter of learning to properly query the AI, getting it to behave in the way we really want instead of what we say we want.

- Our identity is wrapped up in our environment and we’re not yet thinking about how critically entangled our future identities will be with intelligent machines. Who we are will be filtered through our relationships with these machines.

Dr. Wildman summarizes his concerns about the ethics of using AI in the classroom and the workplace well in this comment on Reddit:

“AI is going to be economically extremely disruptive in a host of ways. From that point of view, AI text generation is just the thin end of a very thick wedge. Ironically, most huge economic disruptions have not affected the educational industry all that much, but schools and universities are not going to slide by in this case because they depend (ever since the printing press was invented) on the principle that we teach students how to think through writing. So educators are worried, and for good reason. Beyond education, though, AI text generation and all other AI applications – from vision to algorithms – will change the way we do a lot of what we do, and make our economies dependent on AI. To navigate this transformation ethically begins, I think, with LISTENING, with moral awareness, with thinking about who could be impacted, with considering who is most vulnerable. I think the goodness of the transformation should be judged, in part, on how the most vulnerable citizens are impacted by it.”

Broader applications of AI

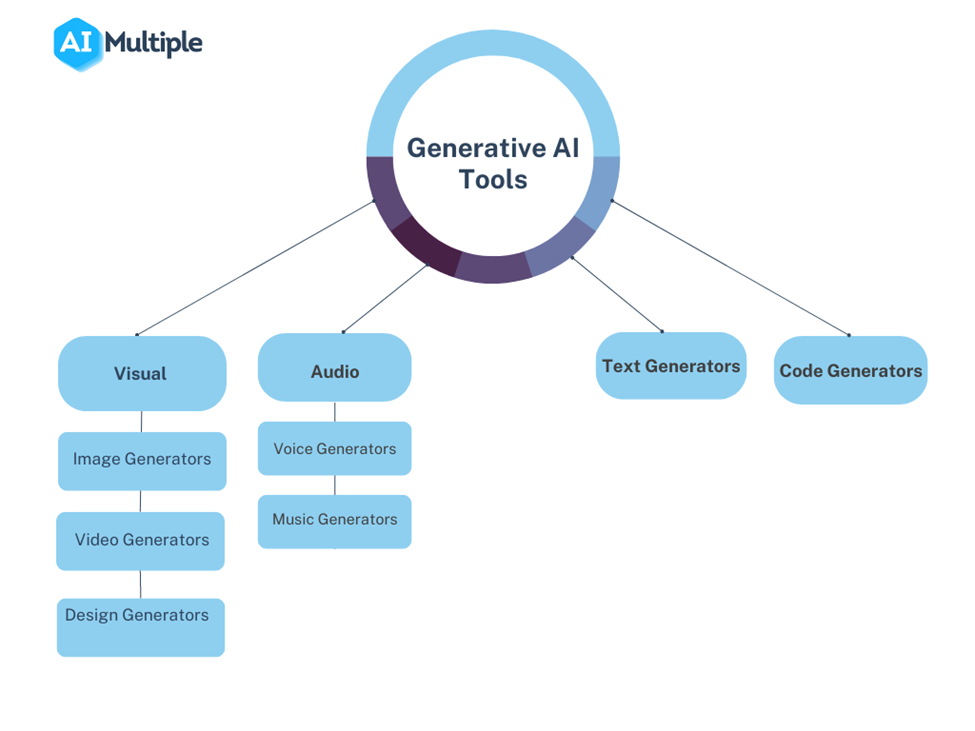

Using AI to generate text is just the tip of the iceberg. As these technologies are rapidly developing, the diversity of their future uses is hard to anticipate; but they are already being used in vastly different ways. Generative AI tools exist to convert text queries into voice, video, music, code, and more.

On HealthMatters, Dr. Wildman gives examples of how AI is being used in the medical field. Machine learning is able to interpret imaging scans and is just as good as humans at picking up subtleties, without the risk of getting tired or distracted while working. AI can be used to screen a patient’s symptoms and direct a doctor to a shortlist of potential diagnoses. Patients in rural areas have innovative access to remote care through responsive chatbots and information streams.

Here at CMAC, we are conducting research on the disparity of suicide rates between rural and urban areas in the US. In parts of the country, a major barrier to mental healthcare is stigma. AI has the potential to become a trusted confidant for some people in crisis who may not feel that they can open up about their struggles to another person, especially someone else in a small community.

Another, more eccentric example of generative AI technology that is already in use is Re;memory by DeepBrain AI. Using about seven hours of interview footage, the developers build a chatbot that can replicate a loved one’s appearance, voice, mannerisms, and more. This is a novel and unprecedented tool for families to cope with the loss of a loved one and continue to feel connected to them.

Going beyond immortalization of family members, AI is taking root in traditional religious practices around the world. In his 2021 book Spirit Tech, Dr. Wildman and co-author Kate Stockly critically evaluate a range of new technologies that assist spiritual experiences. Machine learning and AI tools are already in use to facilitate rituals such as meditation, prayer, confessionals, and funerals.

There are a million things that AI can do to make our lives richer, more purposeful, and more valuable. But we have to be careful to consider what could go wrong, because there are also a million things that AI can do to make our lives worse. We have great trouble understanding complex systems and that means it will be hard for us to predict unintended consequences of AI.