Threads of both vaccine development and vaccine resistance can be found throughout the course of American history. Hesitancy over vaccine development was prominent before the first vaccine was created, and continues to grow today despite technological advancements and refined experimentation. Mandatory inoculation of soldiers of the Continental Army was critical to early American history and was defended a century later in a Supreme Court decision that shapes Covid-19 public health policies today.

Variolation helps to shape the American colonies

The Colonial period experienced numerous epidemics, including measles in 1657 and Yellow Fever in 1699. However, it was smallpox that would become one of the deadliest diseases to the American colonies, with Boston’s significant port at the epicenter. During an outbreak in 1721, there were 844 deaths in the city—almost 7% of the population—and surrounding Native American communities suffered a staggering death rate of up to 90%.

In the wake of this outbreak and others before it, physicians, clergy members, scientists, and civilians were eager to find a way to combat the disease.

Around this time, Onesimus, an enslaved man of West African descent who had recently been purchased for Puritan minister Cotton Mather by his Dorchester congregation, advocated for inoculation against smallpox through variolation. The method involved exposing pus from an infected person to a healthy person’s arm, either by rubbing dried pus or pulling a string through an open wound.

While this process was not a method of vaccination, it was a procedure that would activate a person’s immune system so their body could fight off disease more effectively. Mather became an advocate for variolation and urged physicians and officials to promote the procedure.

However, he received tremendous backlash for his supposedly outlandish ideas. Boston residents argued that inoculation was against the divine law championed in Mather’s own sermons, and many were fearful of the method due to their racial bias against Onesimus and the origins of variolation. Medical professionals expressed disdain for inoculation efforts, believing that variolation was based on folklore and would instead accelerate the spread of smallpox.

Zabdiel Boylston was the only physician in the area who would support Mather’s notion. Together, Mather and Boylston conducted an early clinical trial, inoculating 242 people against smallpox. Boylston was arrested and both he and Mather experienced numerous threats of violence for this.

Yet, numbers from this effort indicated great success, reporting a 2% death rate, while the overall mortality rate of smallpox was 14.8% in the general public. Boylston’s work was recognized in the scientific community and in 1726 he was invited to London to present his study to the Royal Society chaired by Sir Isaac Newton, “representing the very first written record of work that focused on immunization coverage in the American colonies and its association with immunization efficacy.”

Early on, Boston native Benjamin Franklin was a skeptic and critic of the technique. His older brother James was the editor of the New England Courant, which ran campaigns to dissuade the public from getting inoculated. After Benjamin’s young son died of smallpox in 1736, he became committed to the cause, compiling statistics and performing his own mathematical analysis. While serving in England, Franklin published his results in 1759 in “Some Account of the Success of Inoculation for the Small-pox in England and America” with physician William Heberden in London.

Franklin distributed 1500 free pamphlets to the colonies, eventually becoming the most outspoken enthusiast for variolation across the new world. He insisted the pamphlet include detailed instructions so that anyone could administer an inoculation. Franklin’s early analysis of the trial and results is considered a forerunner of biostatistics and observational epidemiology.

Smallpox and the American Revolution

During the early battles of the American Revolution in 1775, George Washington became the commander in chief of the new Continental Army sent to oversee the Siege of Boston. The Continental Army joined the local militia, comprised mostly of farmers and shopkeepers from towns across New England who had signed up after the battle of Lexington and Concord weeks before. This gathering of forces catalyzed the outbreak, as the “war brought men from diverse geographic locations into crowded camps and then exposed them to civilian populations in their travels, expanding smallpox transmission into vulnerable populations.”

By the fall of that year, Boston was experiencing another smallpox outbreak, and many believed the British were intentionally spreading the virus. The occupying British troops had largely been inoculated or survived a past exposure to smallpox, leaving them less vulnerable than the colonists and surrounding Continental Army.

Washington quickly implemented methods of isolating infected soldiers to limit outside exposure, but despite his efforts as many as half his troops were incapacitated due to the disease. In one month of the Quebec campaign, more than 25% of the Continental Army’s 7000 soldiers died from smallpox. Upon hearing the news from Quebec, Franklin feared “that the virus would be the army’s ultimate downfall.”

In desperation, Washington commanded a mandatory inoculation of his army in 1777, despite the medical procedure being banned by many states and the Continental Congress. Infection rates plummeted from 20% to 1%, protecting over 40,000 soldiers during the war and safeguarding their communities when they returned home. Washington’s willingness to adopt a new scientific method allowed the Continental Army to survive long enough to win the war and gain national independence.

The success of variolation during the war paved the way for one of the first pieces of public health legislation in America as inoculation bans were lifted.

The first vaccine pairs with the first anti-vaccination movements

While variolation was proven to decrease the risk of smallpox throughout the 1700s, it was not the safest method of disease prevention.

In 1796, Edward Jenner, an aspiring British doctor, formulated the first smallpox vaccine. Rather than exposing patients to pus from an infected person, Jenner’s vaccine technology used the milder cowpox virus to introduce the disease and prepare the immune system to fight smallpox. Yet as the vaccine started to reach the general public, many English doctors disagreed with the vaccination methodology.

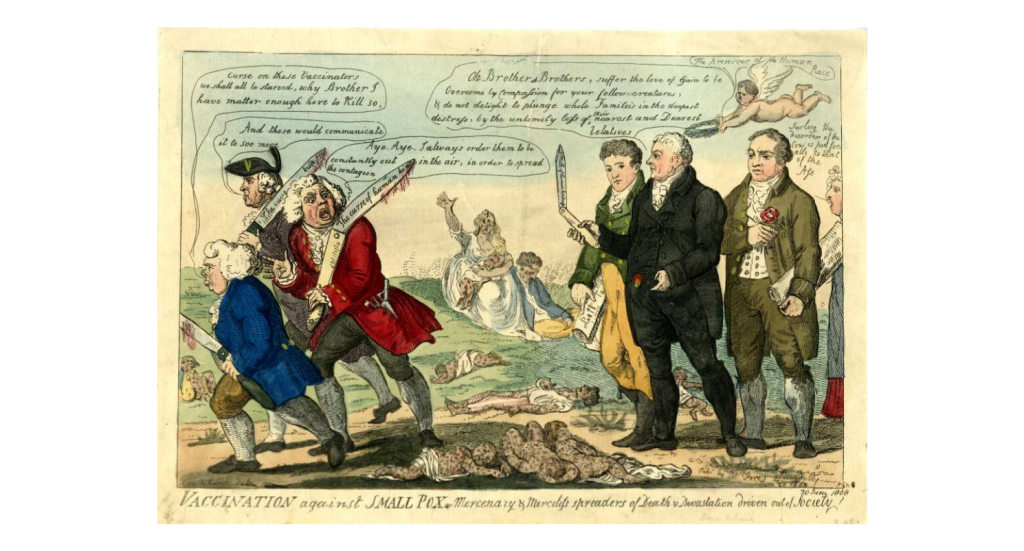

Dr. William Rowley was a fierce opponent of Jenner, producing pamphlets denouncing the credibility of the smallpox vaccine. Rowley listed a series of supposed torpid side effects, including obstruction of typical facial features, blotchy skin, and serious ailments including blindness. He also sensationalized vaccinated patients with horns and other beastly characteristics, and insinuated that the vaccine could cause death.

Another dissident, Benjamin Mosley, argued that the vaccine could cause mental maladies. Even though both Rowley and Mosley had financial motives to block the dispersion and use of the smallpox vaccine (both were trying, unsuccessfully, to develop inoculations), skepticism still prevailed and pervaded the English population.

Throughout the mid-1800s, vaccination methods continued to improve, and the English parliament started to implement vaccine mandates. Civilians were fearful and saw this as an attack on their autonomy, causing protests across the country and the formation of anti-vaccination societies. Since Jenner’s smallpox vaccine was the first vaccine developed, there was no standardized approval process to test its safety. As the procedure was popularized around England, medical practitioners created new vaccine formulas from volunteers who had already been infected or vaccinated in the area. Lack of sanitation and adequate health screening meant that the procedure led to some people, especially children in poor urban areas, being exposed to other diseases such as syphilis when they received the smallpox vaccine.

Much of the anti-vaccine campaign was rooted in theological debates, but there was a portion of the population that was experiencing legitimate and unacknowledged medical harms, fueling additional distrust.

Meanwhile, vaccination had arrived in the U.S., with Harvard professor Benjamin Waterhouse performing the first smallpox vaccination in 1800. By 1809 Massachusetts passed the first compulsory vaccination law. But as vaccination efforts ramped up, so did the opposition.

William Tebb had been part of the anti-vaccination movements in England, and he brought the campaign with him when he later relocated to the U.S. Like Rowley and Mosely in London, he disseminated false information and incorrect data regarding the relationship between children’s deaths and vaccination, influencing the establishment of The Anti-Vaccination League of America in 1882. Tebb was successful in provoking fear among Americans who viewed vaccines as infringements of personal liberties and preferred homeopathic practices.

Boston doctor Immanuel Pfeiffer preached that healthy civilians had nothing to fear from the smallpox disease. Likewise, abolitionist Frederick Douglass argued that vaccinations were an encroachment of freedom of choice, particularly relevant after Thomas Jefferson conducted smallpox vaccination experiments on enslaved children and adults of his household without their consent. The main arguments against vaccines at the time, according to medical historians, were that the vaccine was ineffective, that it had harmful or poisonous chemicals, and that it was a form of medical oppression.

The Supreme Court upholds the constitutionality of vaccine mandates

Massachusetts remained one of few states to require vaccines by the early 1900s, empowering cities to enforce the law on individuals. In 1905 in the city of Cambridge, a pastor named Henning Jacobson declined the smallpox vaccine, asserting that he and his son previously had medical complications due to the vaccine. Jacobson refused to pay the $5 fine at the time, which led to his prosecution as the city filed charges against him.

The case questioned if the mandatory vaccination law breached Jacobson’s civil rights.

In a 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that states indeed had the police power to enforce compulsory vaccination because of the importance of public welfare and preservation of life. In this case, vaccination was reasonable in order to restrain the smallpox epidemic. Under the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment, the Supreme Court further explained that while individuals are entitled to personal liberty, in the circumstance of a medical emergency, those liberties are limited due to the prioritization of the general public’s safety.

The precedent of Jacobson V. Massachusetts prioritized the necessity of certain laws for the common good which set forth the foundation for public health legislation. The case established four standards for a governmental public health measure to be passed. There must be a prerequisite of an emergency needing governmental intervention, the consequential action must be reasonable and proportional, and the action should also avoid harm to individuals’ health.

The implications today

Jacobson V. Massachusetts continues to act as a guide for determining governmental involvement in public health issues. Precautions against the spread of Covid-19 and the emergency approval of the vaccines are supported under the precedent that the general public’s prosperity and protection is valuable. State mask mandates and advisories are also upheld because the 14th Amendment serves to protect public health.

The case’s guidance also continues to receive pushback as people argue that Covid-19 vaccine mandates breach religious freedom, personal liberties, and ethics. Similar arguments were made about smallpox vaccine mandates, and these arguments are finding an audience due to people’s discomfort with cutting-edge medical technology. The technology of variolation and vaccination were cutting-edge at the time, just as the technology of mRNA vaccination is cutting-edge now.

Vaccine hesitancy is not new, and many of the same reasons for hesitation in Colonial Boston exist today. Luckily, researchers have shared their progress with vaccine development throughout the pandemic, allowing individuals to more easily access answers to their questions and concerns. As we face concerns about vaccines and the constitutionality of vaccine mandates once again, we can look to the past right here in Boston in order to shape our future.