The first wave of Covid-19 vaccines

Over the past year, we have witnessed a mass mobilization in vaccination of historic proportion. Lines wrapped around blocks to secure an early shot, sports stadiums opened to accommodate clinics, a frenzy to scavenge for available appointments. This effort has been, like the entirety of the pandemic, unprecedented. Then suddenly, the dust settled, emergency clinics lulled, mass vaccination sites closed, appointments went unclaimed, and large groups of the population remained unvaccinated.

Communications efforts turned their attention to the hesitant, an effort to educate those who were wary, to spread credible information, and to direct people to resources. These campaigns were largely a success; studies have shown that well-targeted public heath campaigning using for example, celebrity endorsement videos, can as much as double a person’s likelihood of choosing to be vaccinated.

In the early roll-out of the vaccine, many hesitant people wanted to “wait and see”. However, the Covid-19 vaccine has proven to be a safe and effective defense against a deadly and stifling pandemic. In late August 2021, the Pfizer vaccine garnered full FDA approval and by January 2022, over 536 million doses of the Covid-19 vaccine had been administered in the US.

Despite these surging numbers, the overall vaccination rate of both adults and children remains largely unchanged in the last three months, with at least a quarter of US adults choosing not to take the shot. In some states the vaccinate rates average even further behind, trailing as low as 53% of the population vaccinated in Idaho.

Many who have gotten the shot see it as a community responsibility to protect one another and an opportunity to stop the virus from mutating, which could lead to an indefinite future of booster shots. They believe they have done their part to end the pandemic and in many cases have become angry and frustrated with those who continue to dismiss the benefits of the vaccine.

In an opinion piece for the New York Times, Miranda Featherstone describes this divide as “warring factions over measures like mask mandates and school closures, with each side minimizing the harms about which the other is concerned. Many of us feel abandoned.” Featherston attributes this anger to misplaced frustration and grief that have resulted from the last two years. People have lost loved ones, lost jobs, and largely felt left behind. This translates into shortened tempers and angers at those who are experiencing the effects of the pandemic differently.

This quick judgement overlooks systemic inequalities including access to information, education, and longstanding social determinants of health.

Understanding the unvaccinated

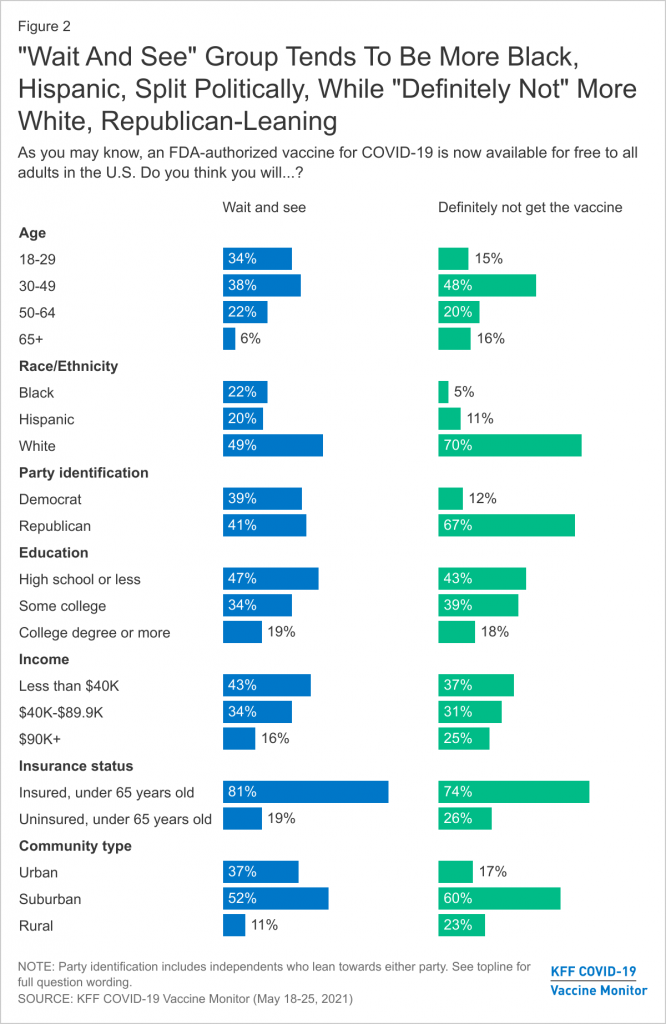

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Vaccine Monitor, an ongoing and largescale survey and research project that aims to understand the public’s opinion toward vaccination, the unvaccinated population is more likely to be from low income, uninsured, and otherwise marginalized communities. They are more likely to have lower access to health literacy and are more likely to fall victim to sophisticated and organized disinformation campaigns.

However, the Kaiser Family Foundation has also been collecting data about the intention to get vaccinated. Taking a closer look at those who are willing to wait and see before eventually getting vaccinated, compared to those who intend to remain opposed, provides more insight into information inequalities.

Those who are willing to get the vaccine after seeing its effect on those who have already been vaccinated are more likely to be populations of color, have lower levels of education, and come from lower socioeconomic status. Those who remain opposed are more likely to be young, white, and Republican.

The survey data shows, “While the share of the U.S. adult population who self-identified as “wait and see” has decreased over the past several months as tens of millions of U.S. adults have received a vaccine and few people have experienced serious side effects from the vaccine, the share of the public who are in the “definitely not” group has not shifted dramatically over the past six months.”

Inequity in information ecosystems

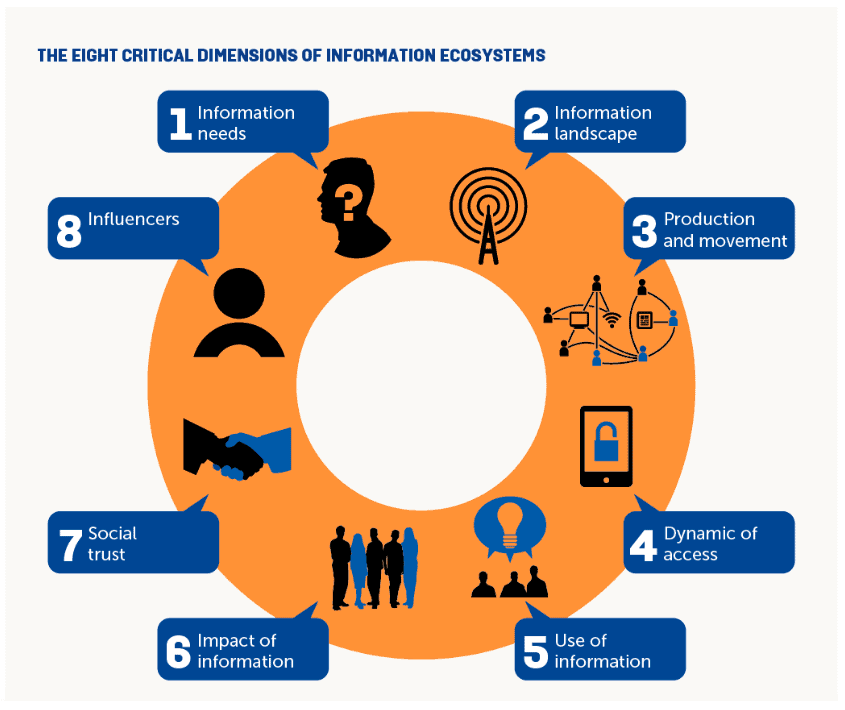

Research shows one of the strongest determining factors in decision-making, including the decision of whether or not to get vaccinated, is an individual’s information ecosystem – the body of information available to them through social circles, peers, media, news outlets, and sources that they may consult. It is what we actively seek out, and it is also what we passively consume. This ecosystem is inherently politicized and classed, and has the capacity to influence our opinions and decision-making processes.

Inconsistent information ecosystems can skew our perception of others and make it harder to sympathize with their experiences. It could explain why the educated elite may have been entirely out of touch with the loss of life due to Covid-19 that vulnerable populations faced on the front lines. It may also be responsible for shaping an uninformed individual’s decision to avoid the vaccine.

The kind and quality of information someone has access to is directly correlated to their socio-economic class, education level, and social circle. For example, someone without health insurance is less likely to have an established relationship with a trusted physician in their network who they are able to seek out or hear from. This type of mistrust is referred to as “inequality-driven mistrust”.

Individuals who have not received the Covid-19 (and other) vaccines are more likely to be victims of sophisticated disinformation campaigns as a result of these inconsistent information ecosystems. “The United States hosts the world’s largest and best-organized anti-vaccine groups,” claims Peter Hotez for Nature. According to the London-based Center for Countering Digital Hate, these are influential groups, not a spontaneous grass-roots movement.

Many far-right extremist groups that continue to spread false information about last year’s US presidential election are doing the same about vaccines. Researchers at NYU have referred to the inundation of disinformation as an infodemic. “This overabundance of information and misinformation contributes to the growing infodemic, where the availability of false or misleading information online and offline creates an environment that can undermine public health responses during a crisis”

Anti-vaccine groups specifically target minority communities, precisely because their limited access to information may make them more susceptible to these kinds of campaigns.

An anti-vaccine documentary, Medical Racism: The New Apartheid, released in March 2021 directly targets the Black community through sophisticated marketing and affiliation with trusted experts, twisting their statements to project disinformation interests. The short documentary has since been deleted, but it serves as an example of disinformation campaigns capitalizing on “a particular moment of heightened national attention on racial injustices and health disparities”.

These campaigns are also targeting Asian American communities through common communication apps such as WeChat, Line, and WhatsApp. These apps allow misinformation to proliferate due to their group message platforms that are difficult to track or regulate. Disinformation campaigns are taking advantage of communities of color who harbor reasonable distrust in medical and government systems in order to find a population to instill with their claims. These online anti-vaccination campaigns build trust through the use of targeted messaging to familiar groups, such as school or community Facebook groups.

Researchers found that 65% of all disinformation surrounding the Covid-19 vaccine could be traced back to just 12 people. The public’s reliance on social media as a news source, as well as polarizing algorithms have facilitated this spread of misinformation. These campaigns have tangible effects on national and global health, further illuminating the ways that access to information, ability to decipher information, and a trusted medical network all contribute to one’s social determinants of health.

The psychology of decision-making

The Covid-19 pandemic has produced a difficult set of circumstances. Correct information and guidance has evolved over time, as we continue to learn more and as the virus itself adapts. This creates confusion; true information can sometimes contradict previously released information, which was true information at the time.

According to Arthur B. Markman, a psychology researcher who specializes in decision-making, this can make the decision-making process around Covid-19 vaccination even more difficult. This is because people are psychologically hard-wired to maintain consistency in our beliefs. Our brain does not like to change its opinion because that threatens our sense of mental coherence. People are more likely to cling to information that supports their beliefs and discount information which contradicts it.

The most effective way to combat this type of disinformation and anti-vaccine ideology is with exposure to evidence and facts. Although the proliferation of disinformation can be discouraging, the only true way to counter it is to continue to share evidence-based research and encourage conversations about the benefits and risks of vaccination.

Lila Norris

Lila is an undergraduate student at Boston University studying Socio-Cultural Anthropology. Through her education and internship experiences she has gained a holistic understanding of culture and media. Lila is interested in social justice and work in the nonprofit sector. After her undergraduate studies she intends to pursue a J.D. in hopes to seek policy based solutions to social justice issues.