Over the past two years, medical doctors and public health officials have been at the center of a national dialogue addressing the physical, communal, and political effects of COVID-19. One dimension of that dialogue concerns the hard fact that pandemic management has left some communities feeling harmed, isolated, and incompetent.

Unfortunately, many clinicians remain unaware of this problem, and how it arises within their patients’ feelings about healthcare. This failure of perception is not new; indeed, it has permeated medical practice, public health policy, and U.S. history.

Setting the Stage

Several years ago, a first-year doctoral student lectured at a day-long seminar hosted by Boston University for community members over the age of fifty-five pursuing unstructured learning. She discussed the necessity of physicians spending more time with patients because more time has been proven to improve patient-physician relationships and empower patients to engage in their personal healthcare decisions.

She cited several positive studies to emphasize the benefits of extended time spent, along with a handful of negative examples that exemplified patients’ distress when spending less than ten minutes with doctors. During the negative examples, a man objected, “These stories are really sad, but that doesn’t happen in Boston. We have some of the best healthcare in the world.”

Another attendee disagreed and fired back with an anecdote about his daughter’s insufficient care. Many complexities framed this tense interaction. The lecturer was a young black woman from the South. The objector was a middle-aged, white native Bostonian. The father was a middle-aged, Asian native Californian.

Did they see differences in care because of their age? Race? Relationships? Personal experience? Location of origin? Understanding of the healthcare system? Whatever the reasons, the exchange exposed rifts between patients and physicians, the need for reconciliation, and the uncomfortable reality that doctors can harm even as they seek to heal.

In a separate lecture on implicit bias in healthcare, the same lecturer spoke with healthcare practitioners to help them understand their potential blind spots in patient care. Many of them struggled to imagine the possibility that patients could be displeased with their care or feel threatened by doctors. They saw care centers as safe havens and doctors as wise and caring experts.

The same general sentiment was evident:

Such medical injustice could never happen here. Boston physicians are trained better; they know better.

Despite the trust many communities and physicians invest in the healthcare system, negative patient-physician interactions are common. Even in environments with a modern and conscious liberality, the balance in power between patient and clinician is always skewed towards doctors.

Patients trust that clinicians understand the medical details and will help them navigate the seemingly insurmountable barriers that block patients from genuine medical autonomy (barriers such as language, complex insurance-provider restrictions, opaque billing systems indecipherable even to the medical professional, and the intricacy of contemporary medicine itself).

As much as contemporary medicine advocates for patient autonomy, it is important to recognize both that we’ve got a long way to go and that this kind of advocacy is relatively new.

In fact, modern medical ethics came about as a consequence of gross medical atrocities at the hands of medical and public health authorities. For all its growth, the medical profession remains firmly rooted in and driven by paternalism.

Here, we follow Dr. Lucija Murgic in defining medical paternalism as a practice whereby, “the physician makes decisions based on what [they] discern to be in the patient’s best interests, even for those patients who could make the decisions for themselves.”

These actions are a direct result of a medical education and clinical culture that overwhelmingly affirms physicians’ perspectives while diminishing patients’ instincts, concerns, lived bodily experience, and desired healthcare goals. This trend even impacts physicians when they become patients. They experience the isolating paternalism that devalues their healthcare needs when the treating physician insists on their proposed treatment plan as the best option.

Most recently, we have seen acute impacts of medical paternalism in the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Inconsistent treatment plans, failure to acknowledge uncertainty, and the exclusion and oversight of vulnerable communities in virus treatment and vaccine distribution has been hidden by the sentiment that doctors “know best” despite the innumerable stories of people who have received insufficient care.

These actions necessitate an historical review of medical paternalism and why simply having trust in medical authorities is insufficient justification for some communities with concerns about the nation’s handling of their health during this global pandemic.

COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy

As COVID-19 vaccines received emergency approval and were administered, medical professionals were confronted with a range of community fears and concerns. Black and brown communities recalled a long list of medical abuses and maltreatment. Mothers recalled clinical dismissal as they advocated for themselves and their children. Many questioned the potential benefits for “Big Pharma.” And many expressed the feeling they were not being listened to and their questions were not taken seriously.

Initially, few medical groups took the time to listen to communal concerns, share information based on their concerns, and support autonomous decision-making. Public health officials and doctors made assumptions and vulnerable communities felt threatened and challenged because their realities were not considered when devising communal health strategies.

We must acknowledge the complexities at play.

On the one hand we have the medical community, desperate to heal the nation but artless in its communications and interactions with diverse perspectives, and ill-equipped for anything but a one-size-fits-all approach. On the other hand, we have individuals and communities with a wide range of legitimate and logical concerns about a vaccine they felt was developed too quickly, with some expressing knee-jerk political reactions based on fear or ignorance.

Over a year after the first vaccines were administered, vaccine hesitancy, more specifically vaccine refusal, remains controversial.

A Twitter thread, initiated by actor Kerry Washington, revealed continued questions around the speed of the vaccine’s development and why it was being pushed so aggressively. Others expressed distrust of “Big Pharma,” listing off many examples of pharmaceutical companies being complicit in harming communities (e.g., the ongoing opioid crisis and the distribution of crack-cocaine in black and brown communities). Some of Washington’s respondents heard family stories about medical atrocities committed against their loved ones, leaving scars of generational trauma.

The conversation was a perfect sample of the ways Americans have wrestled with their health and medically paternalist responses to their concerns. Unfortunately, despite a wealth of data of this kind, pandemic responses remain politically charged, inflected by class, and blocked by intractable forms of vaccine resistance.

How We Got Here: A Brief History

COVID-19 is the first global pandemic most living humans have experienced, but it is part of a larger infectious disease narrative. Prior to the development of antibiotics at the beginning of the 20th century, infectious diseases were common between the 14th and 19th centuries.

The rise in colonization witnessed increased disease movement around the globe. As late as the 20th century, smallpox alone was responsible for 300 million to 500 million deaths. With time, expanding knowledge around diseases and prevention led to new medical technologies and cultural practices, such as quarantine during the bubonic plague, to mitigate disease spread.

One important practice that lasted centuries was variolation. Practitioners would expose uninfected individuals to smallpox pustules, expecting the exposed individual to experience a milder case of smallpox then become immune.

Despite communal benefits, the practice was widely controversial and often rejected in the American colonies until George Washington mandated smallpox inoculations for the Continental Army during a local epidemic in 1777. Smallpox infections dropped dramatically, and anti-variolation laws were quickly repealed, gradually leading to contemporary treatment models of disease and immunity.

Several years later, English physician Edward Jenner developed the first smallpox vaccine from cowpox and Thomas Jefferson championed smallpox vaccination during his presidency. However, skepticism around the vaccine and variolation persisted, leading to anti-vaccination societies, inspired by British anti-vaccination activist, William Tebb.

The Anti-Vaccination Society of America (1879), New England Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League (1882), and Anti-vaccination League of New York City (1885) followed Tebb’s belief that vaccines dirtied the blood and caused diseases. Sanitation, not vaccines, was the only effective practice to stop disease spread. Tebb’s writings inspired anti-vaccination activists to employ large scale media campaigns, distribute anti-vaccination propaganda, and lobby heavily to reduce growing appeals to establish mandatory vaccination laws against smallpox.

Their activism did not deter state and local governments from requiring adults to be vaccinated. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, a local board of health instated a vaccination mandate in response to a local smallpox epidemic. Those who refused without proof of health concerns were fined $5, which was a significant fine at the time.

Cambridge pastor Henning Jacobson refused to be vaccinated, claiming he and his son previously had allergic reactions to the smallpox vaccine. At the same time, he challenged the constitutionality of the order in court, even though it had a built-in exception for people with valid medical concerns.

Jacobson argued that he had no duty to be vaccinated or provide reasonable proof of medical exemption, and that the state of Massachusetts had no right to fine him for refusing the order. But the court’s decision supported the use of police powers to protect the health of constituents, and further explained that the personal liberties of an individual were not absolute: an individual’s right not to be vaccinated did not override another’s right to be free from disease.

Jacobson v. Massachusetts was a landmark case that would be cited and interpreted for years, often supporting state power to determine health decisions. On its face the ruling was sound.

Public health interests were balanced by individuals’ personal liberty; medical exemptions from vaccination were protected for those with legitimate medical conditions; and, penalties could be levied against those who refused, but mandatory vaccination could not be enforced.

But that decision has continued to add fuel to anti-vaccination campaigns and medical distrust, especially in the past two years as the Jacobson case has been invoked to support facemask and stay-at-home orders.

From Vaccines to Bodily Harm

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the use of police powers in public health and the rise of medical paternalism intensified beyond vaccination campaigns to eugenics. In 1896, Connecticut established marriage laws that deemed it illegal for “people with epilepsy or who were ‘feeble-minded’ to marry.” Approximately a decade later, the American Breeder’s Association (ABA) was established to focus on controlling human heredity to reduce the threat of “inferior” humans.

ABA was the first national eugenics organization for professional scientists and clinicians, paving the way for such groups as the Race Betterment Foundation, the Galton Society, the Eugenics Records Office, and the American Eugenics Society. These organizations relied heavily on crafting medical procedures and scientific justifications for their typically racist ideologies, which harmed generations of people, especially communities of color and women.

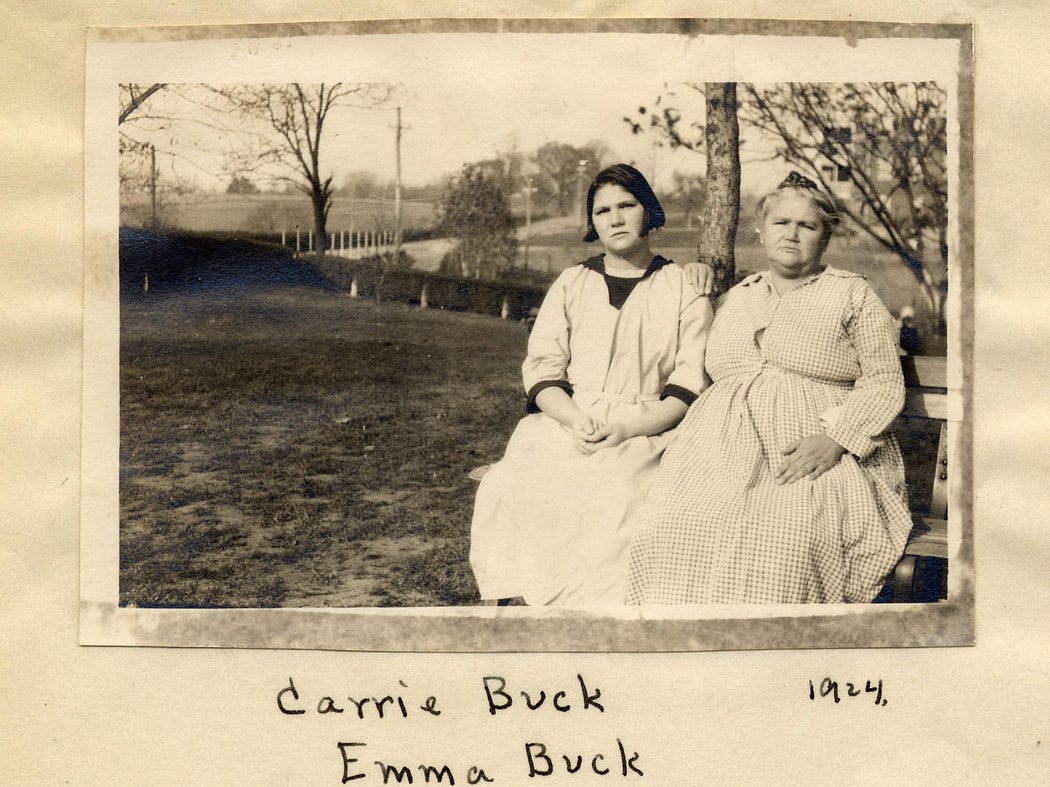

Eugenics societies led to the forced sterilization of women from “undesirable” backgrounds, and even received judicial support in the case, Buck v. Bell. Carrie Buck, a young woman from Virginia, was the first of approximately 8,000 people to be forcibly sterilized under the state’s eugenics law between 1927 and 1972.

Years prior, Carrie’s mother was diagnosed as feeble-minded and sent to the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded in Lynchburg. Her mother’s displacement resulted in Carrie living with a foster family where she eventually became pregnant, resulting from rape by the family’s nephew. Carrie’s “sexual predicament” led to her diagnosis of feeble-mindedness. She was sent to the colony with her mother and there was chosen as a test court case to approve sterilization across the state.

At the state level, doctors won the case and sterilization laws were upheld, but Carrie appealed to the Supreme Court. There, Oliver Wendell Holmes justified forced sterilization for the public interest, claiming that the government should not bear the burden of an inherited disability. “[T]hree generations of imbeciles is enough.”

In reviewing Carrie’s case, most experts have come to believe that neither she, nor her mother or sister, were feeble-minded or epileptic. Yet white men stripped them of agency to guard their bodies from a medical culture that deemed them undesirable.

Across the U.S., an estimated 70,000 women were sterilized following Buck v. Bell. The reasons given for sterilization were that they were “mentally deficient,” disabled (e.g., the deaf, the blind, the sick), Native American, or African American. Although the practice eventually ceased, the Buck v. Bell decision was never overturned by the Supreme Court. We have even seen the justification for sterilizations shift from feeble-mindedness to immigration as women in ICE custody have undergone alarming rates of hysterectomies, which is currently under investigation.

Alongside Carrie Buck, Henrietta Lacks was another victim of medical paternalism. Lacks, a young woman suffering from cervical cancer in 1951, went to Johns Hopkins seeking treatment for her vaginal bleeding. Doctors retrieved a sample of cervical cancer cells, treated her with radium, and sent the cells to researchers who discovered that her cells doubled approximately each day.

She unknowingly became the progenitor of the HeLa cell line, which has been used “to study the effects of toxins, drugs, hormones and viruses on the growth of cancer cells without experimenting on humans. They have been used to test the effects of radiation and poisons, to study the human genome, to learn more about how viruses work, and played a crucial role in the development of the polio vaccine.”

While Johns Hopkins pays homage to the contributions Lacks’ DNA made to scientific advancement, that acknowledgement comes years after her family fought to ensure her humanity and life were shared, as well as that future patients exert the right to consent to any cellular research benefiting from their DNA.

Challenges to autonomy and consent are also prevalent for birthing people during labor and delivery. Some patients have experienced what is increasingly becoming recognized as obstetric violence because they lost power struggles with their clinicians. Their experiences have included forced and coerced cesarean sections, medical racism, and alarming healthcare disparities and inequities disproportionately impacting black, brown, and indigenous birthing communities.

The history of toxic medical paternalism is not limited to bodily harm but also extended to mental health as psychosurgery prioritized people who were uncontrollably violent or were confined in mental institutions. For years, individuals considered “untreatable” due to mental illness were forcibly lobotomized and left with irreversible personality changes.

The inventor of the lobotomy went on to win the 1949 Nobel Prize in Medicine. Other physicians even found ways to hasten the procedure, claiming the desired outcome was to produce more easily manageable patients in institutions. The patients had neither the agency to determine what was “manageable” nor pathways toward “manageable” status.

A serious outcome of lobotomies was the silencing of “troublesome” family members and “agitated and boisterous” women. Even today we see the legacy of removing agency for women through conservatorships, which includes financial and medical decisions.

Race and Public Health

Marginalized communities, like the aforementioned women, experience intersectionally compounding levels of oppression that have informed their strained relationships with medical professionals.

One of the most infamous representations is the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972). In 1932, the Public Health Service started recruitment for a syphilis study from a predominantly African American community in Macon County, Alabama. While the study began with seeming integrity to monitor the natural history of syphilis, roughly a decade into the study penicillin became available as a treatment.

However, researchers and doctors did not offer penicillin to study participants but continued monitoring symptoms. Decades passed before the study ended, only as a result of journalism revealing that the participants were harmed by having treatment withheld.

These doctors and public health officials enforced paternalism by choosing what care, or lack thereof, was best. Those same officials were respected by society so much that their dangerous and unethical ideologies, impacting vulnerable communities especially, were not challenged for decades. And these professions have yet to make the necessary amends and changes in practice that would boost trust and lead to better relationships.

This lack of action creates space for targeted misinformation that continues to exploit historical medical traumas and deepen distrust between communities of color and medical professionals. The recent anti-vaccination campaign by RFK, Jr. does exactly this, manipulating historic fact to target Black citizens’ medical fears and distrust. Unfortunately such campaigns often succeed because they offer what doctors often do not: acknowledgment of harm.

Examples of patients feeling unheard and marginalized communities feeling mistreated, threatened, and under-treated are not relegated to history. Black people are routinely undertreated for pain, there is trans discrimination in healthcare, and the healthcare infrastructure for Indigenous communities is so weak that they continue to die at higher rates than most other racial/ethnic groups.

Many communities’ contemporary health inequities are direct products of a medically paternalist culture of neglect and under-treatment. Medical professionals continue to rely on the privilege given them through their education and social status to prioritize their moral and cognitive judgment instead of deeply listening to their patients and their embodied experiences.

As individuals and communities fought against the threat of medical harms, widespread anti-vaccination sentiment returned during the late 20th century. The Lancet, a highly regarded, peer-reviewed medical journal, published a small preliminary study by Andrew Wakefield claiming that a number of children injected with the Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccine developed autism and gastrointestinal disease.

Although the paper was retracted twelve years later following a journalistic investigation that uncovered funding for Wakefield’s research by parties already pursuing litigation against vaccine manufacturers, the long-term damage was done. Anti-vaccination movements rallied behind the fears that measles vaccinations could cause autism. One result has been large outbreaks of measles throughout the U.K., Canada, and the U.S. Another has been the intensification of vaccine hesitancy, which has directly impacted COVID-19 pandemic management.

The Wakefield paper provided the anti-vaccination community surface-level academic support, but their concerns and fears are a part of the larger narrative of medical distrust stemming from the individual and communal abuses committed by medical and public health professionals.

What Can Be Done?

As was the case in Jacobson v Massachusetts, politics and public health remain controversially connected as people determine ways to protect individual liberty, bodily integrity, and public health. And that politicization has become core to American identity throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

But two things remain clear from U.S. medical history: communities have decades of experience informing their skepticism and hesitancy toward medicine and public health, and medicine and public health must work collaboratively with communities to strengthen trust and medical practice.

Medical professionals must change the medical paradigm to encourage large-scale behavior shifts. Medical professionals must listen to their patients and manage clinical paternalistic behavior, thereby inspiring trust and honesty. They must also confront their engagement in an educational and professional culture that asserts their dominance and diminishes the lived existence and autonomy of their patients.

In the early weeks of COVID-19 spread, many doctors and public health experts felt like they were flying blind because they had no firm solutions for treating COVID-19 symptoms. As COVID-19 has normalized, paternalism has returned and some patients have suffered because of doctors’ choices. The medical community can no longer support a culture that “doctors know better” when that professional knowledge and training is exercised at the expense of their patients and their home communities.

Many of the problems that the medical community laments — including those blamed on the lay public’s lack of medical knowledge or understanding — have roots in the betrayal of vulnerable patients by medical practitioners. Those who insisted they knew better enacted egregious harms and now blame the harmed for justifiable concern.

Approximately one-third of Americans remain hesitant about the COVID-19 vaccine, and a large share of those who got vaccinated did not do so because they trusted the medical establishment. They cared about reuniting with their loved ones, protecting their vulnerable family members, and sharing their favorite public spaces with their favorite people. The success of early COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, especially those that centered around education and personal choice, was rooted in the longing for a return to some semblance of normalcy — in some cases, despite medical distrust.

Medical professionals need to reassess their engagement with their patients and communities, whether they are fighting off a novel virus or offering routine care. A first step is recognizing patient autonomy in treatment plans and bodily health. A second step is recognizing that medical professionals haven’t had, and still don’t have, all the answers.

Written by shaunesse’ jacobs, Nelson Wu, and Gretchen Weaver