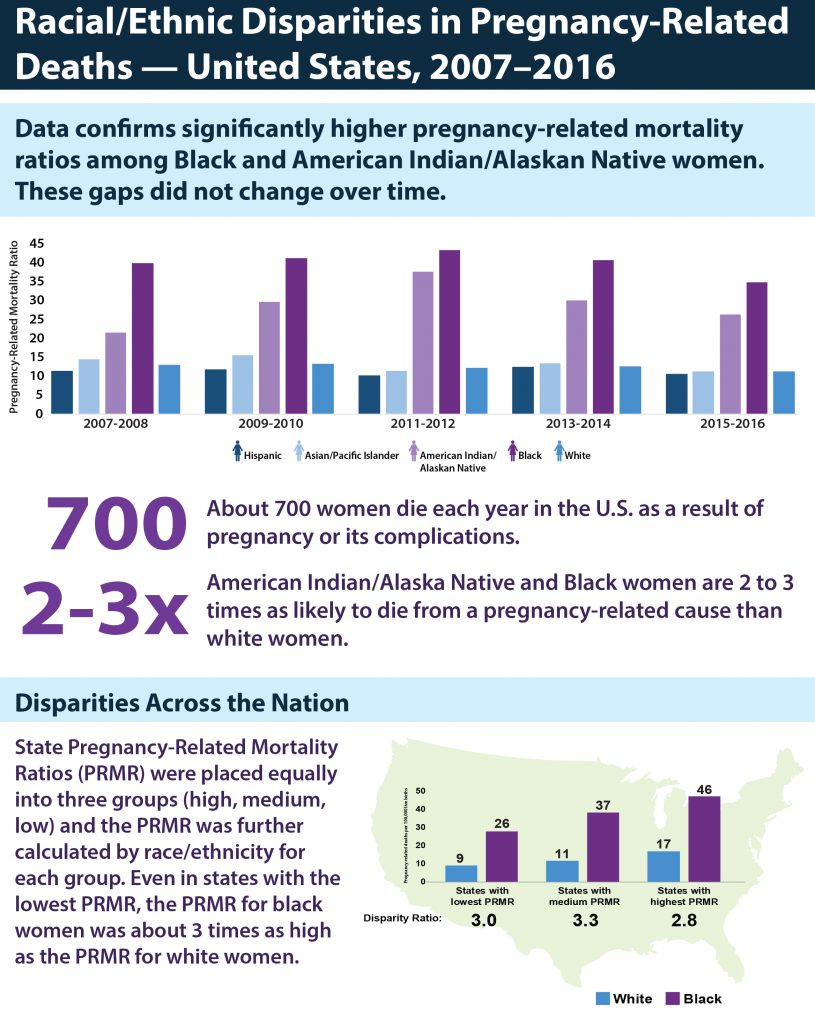

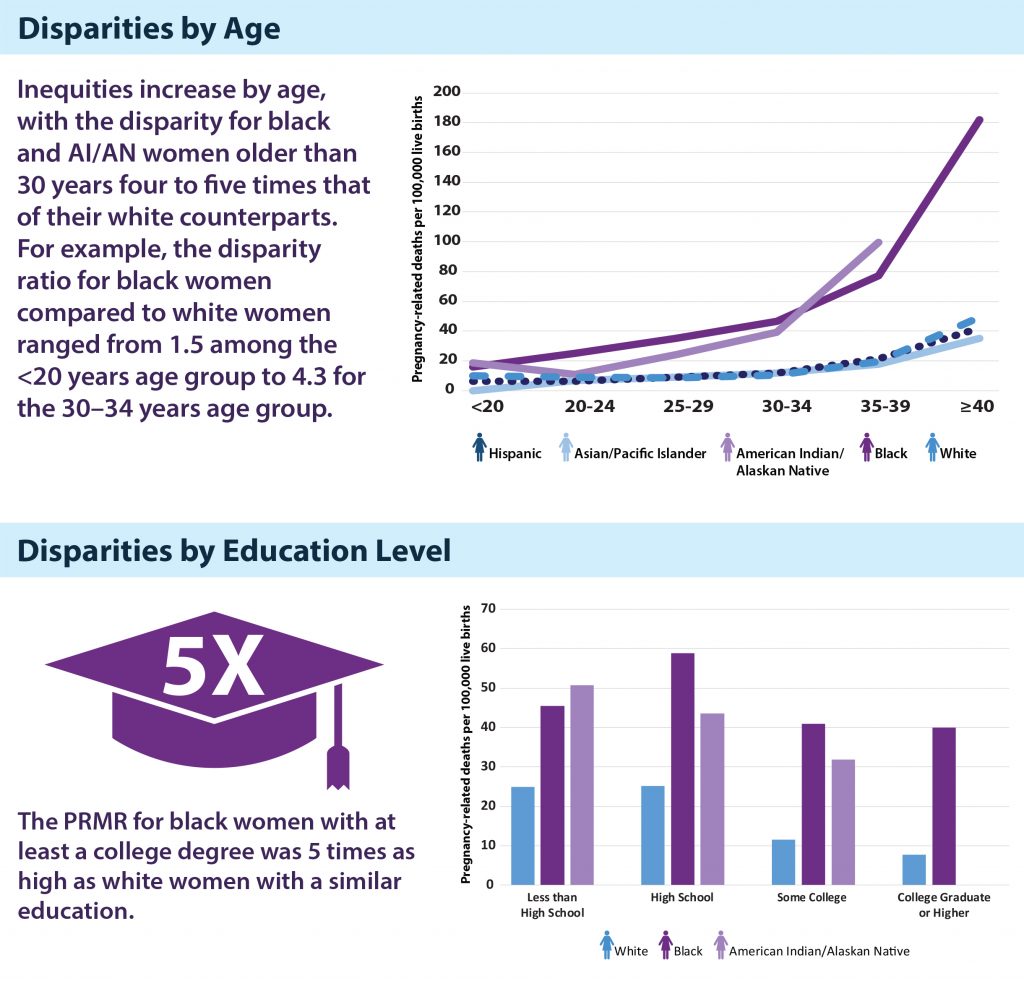

One of CMAC’s newest projects is Black Maternal Mortality, which is looking at data from Boston hospitals to learn more about the underlying conditions that cause maternal mortality rates to be three to four times worse for Black mothers than other mothers in the U.S. This project is lead by shaunesse’ jacobs, a PhD candidate in Constructive Theology and Ethics at Boston University. In order to provide context on the project and shaunesse’s research, we had a conversation with her about her background in academia and research, why this project matters to her, what the project will look like, and resources for those interested in learning more.

Tell us a little about your background and your path in academia/research. What’s lead you to where you are and what your research interests are today? How did you get started pursuing data in black maternal mortality?

All parts of my story begin in Shreveport, Louisiana, where I was born and raised by my mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother. My great-grandmother was a sharecropper during her early years and only attained a sixth-grade education because her father needed help with her four younger siblings and ailing mother. Because she couldn’t complete her education, she wanted nothing more than for her children to be well-educated. Her influence, along with my grandfather’s travels beyond Louisiana with the Air Force, played important roles in my mother’s education and parenting as she pushed for my sister and myself to attain the highest level of academic achievement possible.

Each of these people figuratively carried me to Atlanta where I attended Emory University for my undergraduate and graduate studies. Initially, I wanted to attend medical school but found myself fascinated by the academic study of religion and the way religion and medicine intersected in ways few people around me were discussing. My religion major turned into a dual master’s in theological studies and biomedical ethics as I focused on issues of ability/disability and end of life care. My father had just survived a hit and run accident while cycling, which left him paralyzed from the chest down. This experience opened my eyes to systemic issues of racism and ability discrimination within the healthcare system.

After completing my program, I worked at a healthcare consulting company reviewing medical records and patients’ claims. While reviewing records, I came across innumerable cases of Black women’s pregnancy-related care not being covered because the conditions that led to their complicated deliveries were not considered medically necessary. The more records I read, the more questions I asked. The more questions I asked, the more unfulfilling answers I received. I began doing my own research and discovered several grassroots organizations dedicated to addressing racial injustice in our healthcare system.

I also found dozens of news articles of high-profile Black women who died or nearly died at various stages of their pregnancies and/or deliveries because they weren’t believed when sharing their complications. These stories led non-celebrity women to share their near-death experiences via social media. While there were numerous anecdotal stories shared within Black women’s communities, very little data supported their lived experiences. Even my own mother shared her fear of dying delivering my sister and myself. She feared doctors would dismiss her concerns and her voice would be unheard. At that point I decided it was important for me to honor my family’s value in education and pursue PhD studies to gain additional skills to conduct the in-depth research needed to understand and help address the systemic medical injustices suffered by Black mothers.

What are the facts the public needs to know about black maternal mortality? How does the data differ between the U.S. and other countries in maternal mortality and specifically in black maternal mortality?

- Pan-ethnic communities are grouped under one banner in most public health data, meaning the data doesn’t capture the ethnic variances within Blackness. For example, statistics on Black maternal mortality and morbidity don’t distinguish Haitians from Jamaicans from Nigerians from African Americans. I believe these ethnic variances conceal important information about other intersectional markers that might inform current morbidity statistics.

- The percentage of maternal mortality across racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. is overwhelming. Earlier this year, the CDC published a report listing the U.S. as 55th in the world in maternal mortality. With approximately 17 deaths per 100,000, the U.S. lags behind fifty-four countries where women have a better chance of surviving pregnancy-related complications. While these numbers are poor for all women living in one of the most developed countries in the world, the systemic racism unique to the U.S. makes matters worst for Black women. Due to pregnancy-related complications, Black women die three to four times more frequently than white women. Issues of racial discrimination exist in other racially pluralistic societies, but the U.S.’s long and continuing history of racism greatly exacerbates the problem.

- While the CDC has been monitoring maternal mortality statistics since 1986, there are few national policies aimed at bettering maternal care and reducing the increasing number of deaths due to pregnancy-related complications. This is reflected in the increasing rate of maternal mortality, spiking from 7.2 deaths per 100,000 in 1986 to 16.9 deaths per 100,000 in 2016. Currently, only twenty-three states have maternal mortality review boards. Most attention brought to the issue is conducted by local, state, and/or national non-profit organizations (e.g. Black Mamas Matter).

How do you see religion and theology as a part of this issue?

According to Pew Research data, Black women in the U.S. are one of the most religiously affiliated demographics in the country. These statistics pique my interested in the ways Black women’s religious expressions help them make sense of the injustices they suffer in the healthcare system. Drawing upon religious and theological ethics is crucial in affirming the inherent human dignity and right to life of Black birthing women, and for calling on wider society to take responsibility for bettering maternal mortality and morbidity outcomes.

Religious and theological ethics also helps me articulate the absurdity of marginalized communities still having to struggle to secure basic protections and a good quality life in one of the world’s leading democracies. I am grateful for the work of generations of womanists before me who began the empowering work towards Black women’s justice. They inspire me today as I dedicate my research to empowering people to continue enhancing their lived experiences.

What stage of the project are you in now and what does that look like?

I’m currently completing an extensive literature review, annotated bibliography, and grouping/tagging of the existing research as I await IRB approval to conduct quantitative analysis of medical records from a local hospital. The literature review involves many hours reading articles and books that address maternal mortality and morbidity in the U.S. Understanding what has been written is essential preparation for making an important contribution to existing literature.

A crucial part of this research involves combing through clinicians’ documented requests since the 1960’s to change maternal care in order to reduce the number of Black women dying from pregnancy-related complications. As I read, I sort and group these documents based on the themes they share, which then helps me understand how the narratives around maternal mortality have been constructed to date.

What outcomes do you want to see come out of this work?

Upon receiving IRB approval and the medical records, I hope to determine the maternal mortality and morbidity narratives in the Boston area. I believe the medical records analysis and literature review will give voice to the gaps in current reporting, from clinical care given to notation and monitoring of symptoms in the records. These gaps will inform various policies that can be created to address adverse pregnancy-related outcomes.

The CMAC team will also use computational policy simulation and modeling to discern which kinds of policies will most effectively address these problems. I hope these models will inform future research projects that address systemic injustices and lead to future policy, education, and care proposals that address pregnancy-related complications and ultimately reduce the maternal mortality and morbidity statistics in the U.S., beginning with Boston. I also hope the research can be paired with other current projects, because much work is being done in siloed communities that could be bridged to create further reaching positive change.

What are the best resources to learn more?

“Birth Equity Resources,” California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative: https://www.cmqcc.org/qi-initiatives/birth-equity/resources

“Structural Competency Meets Structural Racism: Race, Politics, and the Structure of Medical Knowledge,” Virtual Mentor: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25216304/

“Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity Prevalence and Trends,” Ann Epidemiol: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30928320/

“Obstetric Racism: The Racial Politics of Pregnancy, Labor, and Birthing,” Med Anthropol: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30521376/

“Health care disparity and state-specific pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2005-2014,” Obstetrics & Gynecology: https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2016/10000/Health_Care_Disparity_and_State_Specific.25.aspx

“Reproductive injustice: Racial and gender discrimination in U.S. health care,” Center for Reproductive Rights, Sister Song, National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health: https://www.mhtf.org/document/reproductive-injustice-racial-and-gender-discrimination-in-u-s-health-care/

“Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: Prevalence and determinants,” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology: https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(09)02002-X/abstract

“Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care,” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology: https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(15)00870-4/abstract